Palma:

Animated By The Same Light

Texts: Joan Miró & Josep Lluis Sert

Photography: Pascal Alexander

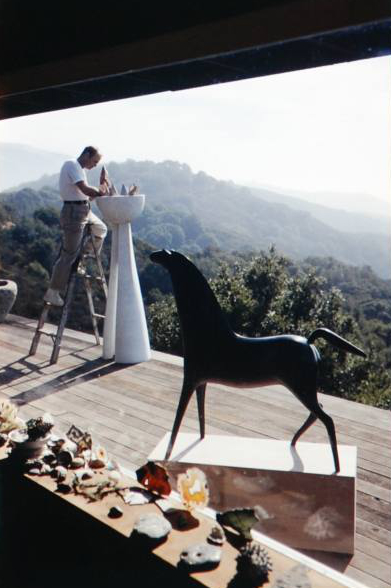

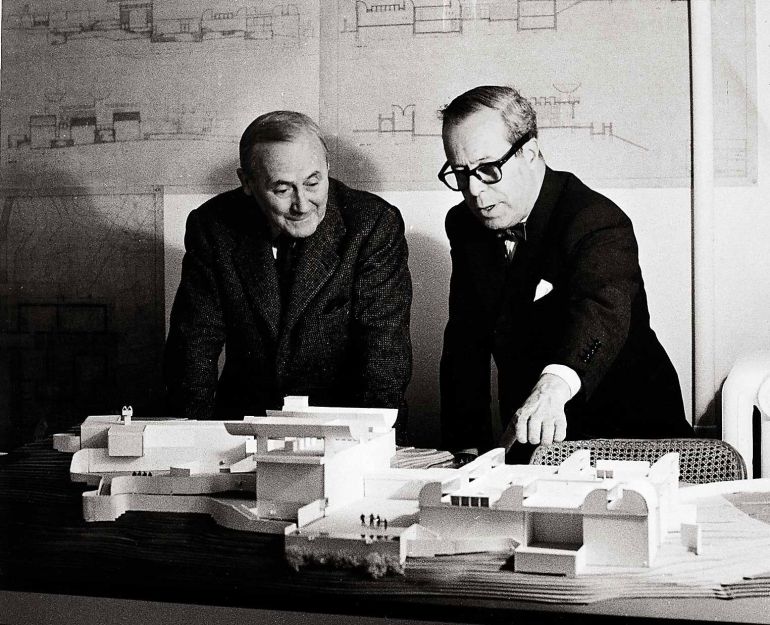

In 1954, after years of incessant travel, Joan Miró settled down in Mallorca and began an intense correspondence with Josep Lluis Sert on the design of his new studio. They met in the early 1930s and long-lasting personal and professional ties were forged, based in particular on their desire to integrate art with architecture and their interest in simplicity as a means of capturing the very essence of things. For Miró‘s studio, a turning point in his career, Sert maintained the importance of function by avoiding the limits of functionalism and emphasizing a more sculptural and visual architecture true to his idea that architecture itself can become a sculpture.

Barcelona, January 18, 1954

Dear Josep Lluis,

I've been awfully busy over the past few days with Pierre, Patricia, and Maeght visiting; now I can finally relax a bit. The ideas you sent me in your letter of the 9th of this month strike me as very appropriate, and will make the building even more beautiful. What I would suggest is that you take into account the climate in Mallorca. It's hot in the summer, and the studio has a large surface area, which is difficult to heat, particularly bearing in mind that I start working very early in the morning. Even if I work on small pieces, there will be where I do all my painting, to set the mood. We were just in Palma for a few days and everyone is working hard. Enric thoroughly agrees with everything you tell him. You know how respectful he is; he wouldn't dream of changing anything without checking with you previously. The engaged couple are very happy, and we are all very pleased to know you'll be visiting this summer. Now I'm making arrangements for sending the latest canvases to Paris and NY. Once that's done, we'll go spend a few days in Montroig to get some ceramics under way. Towards the end of this month or early February Pilar and I will be going to Paris for two months. I'll keep you posted about our whereabouts.

Much love to you and Moncha,

Joan

Dear Josep Lluis,

I've been awfully busy over the past few days with Pierre, Patricia, and Maeght visiting; now I can finally relax a bit. The ideas you sent me in your letter of the 9th of this month strike me as very appropriate, and will make the building even more beautiful. What I would suggest is that you take into account the climate in Mallorca. It's hot in the summer, and the studio has a large surface area, which is difficult to heat, particularly bearing in mind that I start working very early in the morning. Even if I work on small pieces, there will be where I do all my painting, to set the mood. We were just in Palma for a few days and everyone is working hard. Enric thoroughly agrees with everything you tell him. You know how respectful he is; he wouldn't dream of changing anything without checking with you previously. The engaged couple are very happy, and we are all very pleased to know you'll be visiting this summer. Now I'm making arrangements for sending the latest canvases to Paris and NY. Once that's done, we'll go spend a few days in Montroig to get some ceramics under way. Towards the end of this month or early February Pilar and I will be going to Paris for two months. I'll keep you posted about our whereabouts.

Much love to you and Moncha,

Joan

Palma, March 30, 1957

Dear Josep Lluis,

The studio is stunning. Angel did a very good job with the shelves, following your instructions. The only problem we've had is the waterproofing of the vaulted roof. It had been covered with the usual white coating, which is normally enough, but we had some unexpected rainstorms, stronger than we'd seen in 30 years, and the sealant wasn't enough. A new, very solid solution had to be prepared, and that called for some background research and then applying several juxtaposed coats at intervals, leaving time for each one to dry. They're applying the last white coat now, and I think it'll work. That's why it took me so long to write; I wanted to see how it worked out. What with one thing and another, I haven't yet man-aged to even out the pace in my work and my life. I needed a long period like this, of long, quiet reflection, only interrupted by the UNESCO work. I'll come out of it with renewed strength and potential.

I've been placing traditional ceramic pieces and fishing gear around the studio and the courtyard. Everything seems enormous, and that will lead me to a new visual conception, a grandiose one, because of the atmosphere in the studio and the poetry and light in the landscape. I've already had many visits from friends from Europe and America and they're all very impressed by the studio. A few days ago Maeght was here; he wants to talk to you about building a museum.

Love to both of you,

Joan

Letters from Joan Miró to Josep Lluis Sert, held in the Josep Lluis Sert Collection, Special Collections Department, Frances Loeb Library of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (E64).

The best basis for a real integration between painting, sculpture and architecture, is a thorough understanding between the architect and the painter, the sculptor or the painter-sculptor. This understanding presupposes community of views, frequent exchanges of ideas, communication and friendship. On the painter's side it also requires an interest in and awareness of space and space relationships, the behaviour and nature of materials and their texture, and last, but not least, the treatment of light — as it is the lighting, natural and artificial, that makes everything that is visual alive. Mural painting is in many ways an old-fashioned term that brings back to our minds the buildings of other times, heavy and unchangeable, with noble masonry walls and rigidly enclosed spaces. It reminds us of renaissance rooms, frescoed from ceilings to floors, where architecture (both fake and real) merges into painting and sculpture without clear lines of demarcation. It was sometimes beautiful, at others unbearable and unliveable, entirely unthinkable today. The paintings that can co-exist with modern buildings as an essential part of them have to breathe the same spirit as these buildings and become animated by the same light. Only an understanding at the start, between painter, sculptor and architect, can result in a totality or a whole.

I have known Joan Miró, for many years — the painter, the sculptor and the youthfulness he carries inside him. This youthfulness (childishness to those who do not understand him) makes him always see things differently, new and alive. The world of Joan Miró is one of constant search and discovery. His interest ranges from the smallest object to the vastest spaces, encompassing a limitless world of whose relationships he is especially aware. His attitude toward painting in many ways parallels that of the space-traveler. His great contribution consists not only of what he puts onto his canvasses, but also of what he does not put there. The open spaces between painted areas, the silent voids, are the best portions of some pictures. His keen eyes can put different objects (of the most varied natures) into their proper relationships, at the right place and right distance from each other, as no one else can do it. Give him a pile of junk, and a Miró will soon be assembled, it will come to life. This facility for relating is an architectural quality, or approach, that makes him especially well suited to move at ease in vast spaces with an awareness of their scale.

Written by Josep Lluis Sert, originally published under the title Miró. Peintures pour des grands espaces in Derriere le Miroir, issue no. 128, Maeght Editeur, Paris (1961).

Written by Josep Lluis Sert, originally published under the title Miró. Peintures pour des grands espaces in Derriere le Miroir, issue no. 128, Maeght Editeur, Paris (1961).

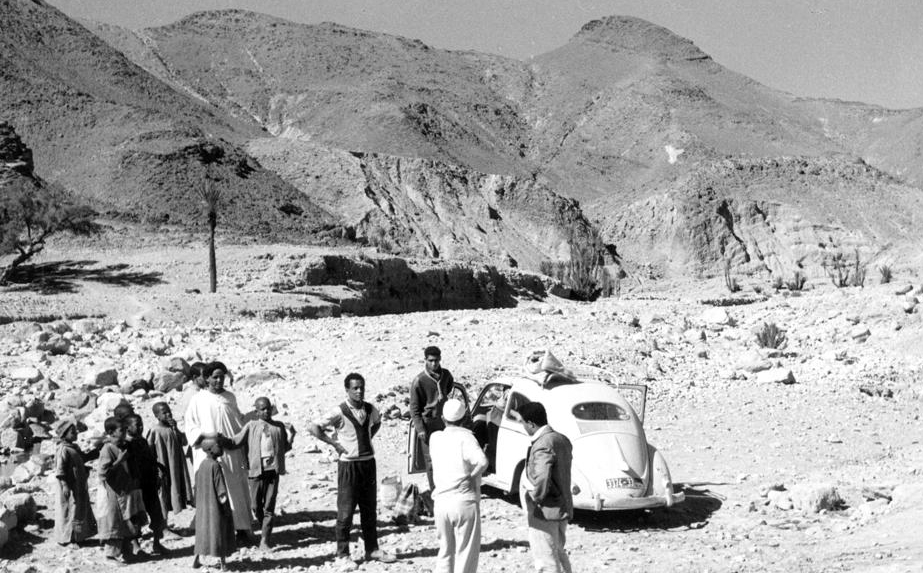

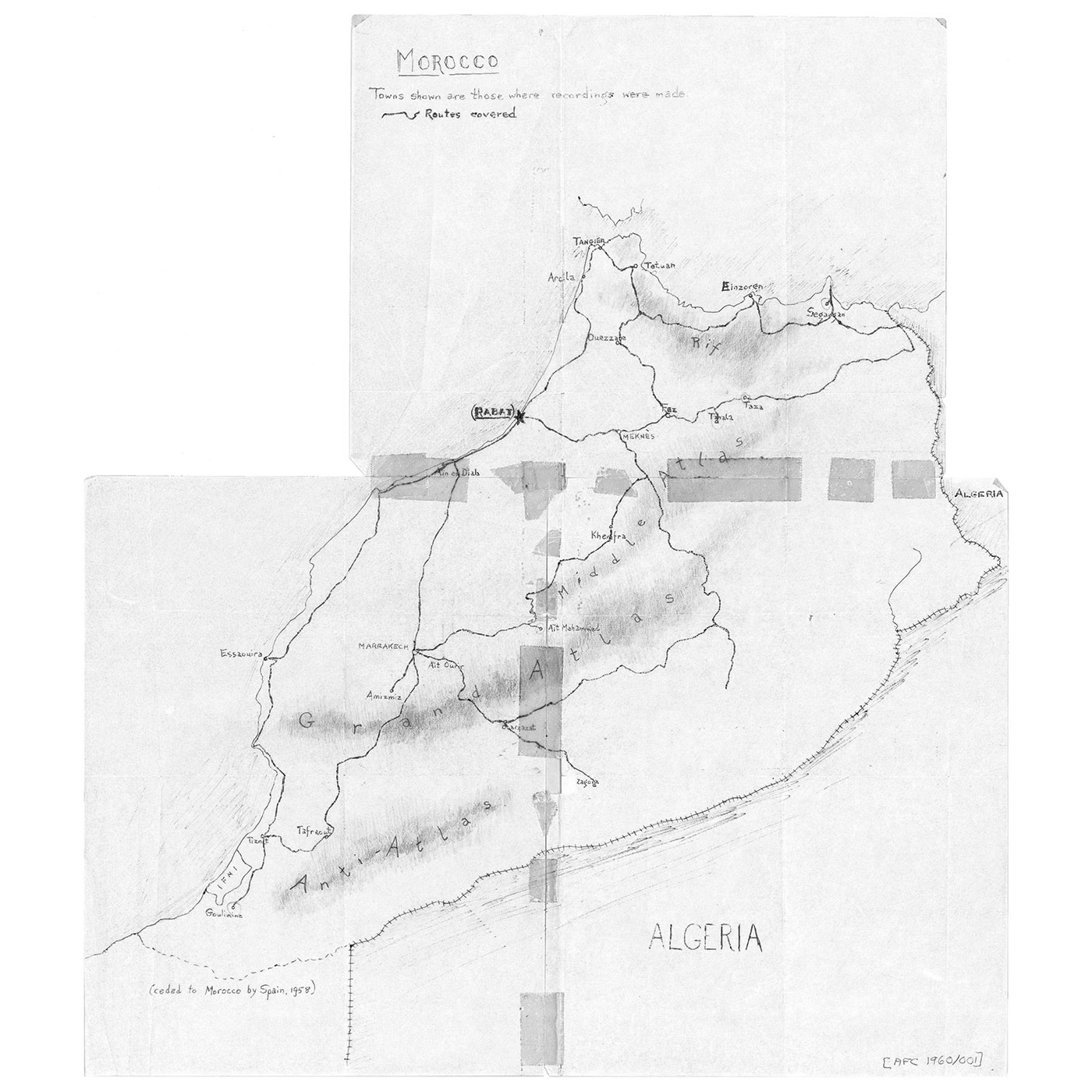

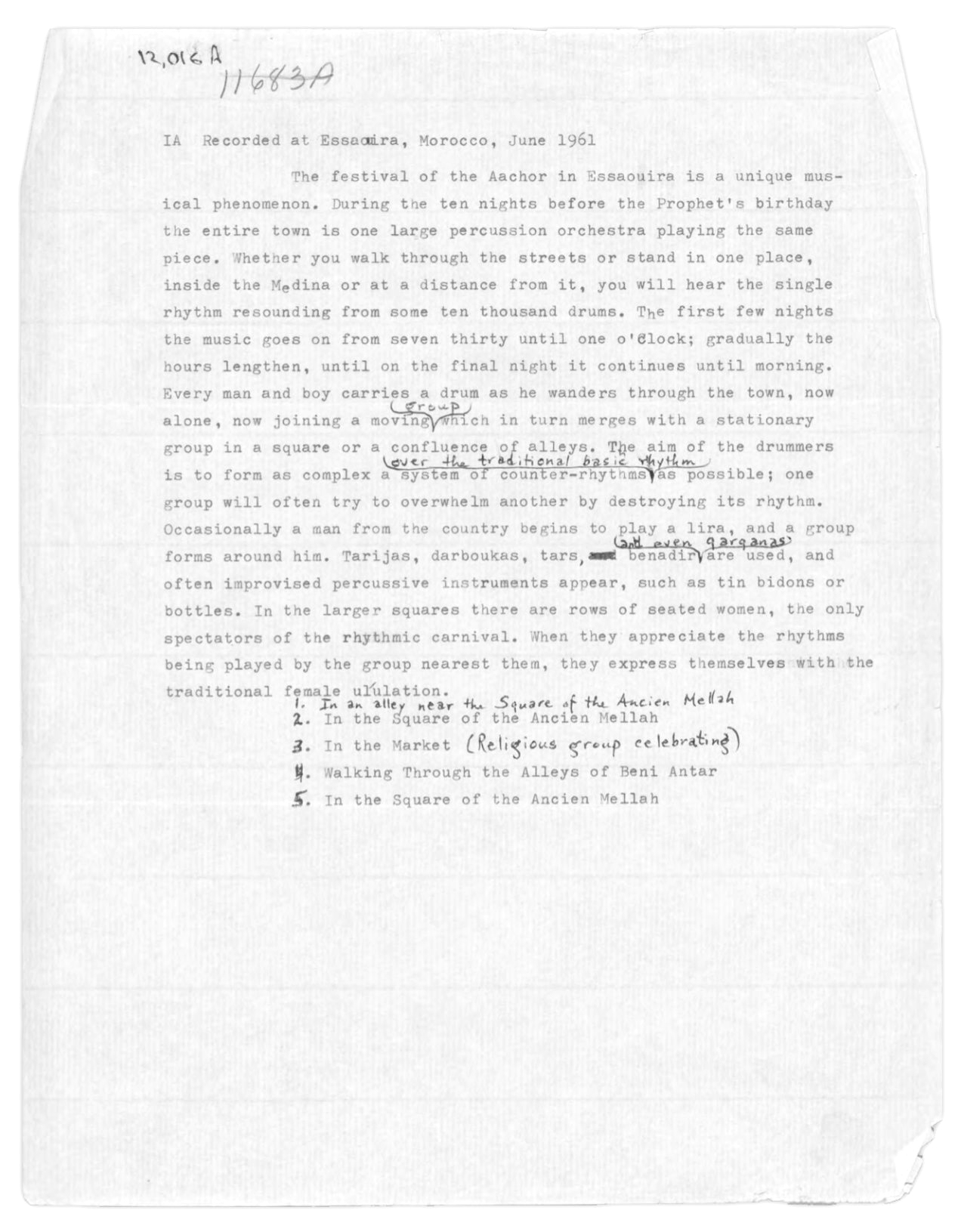

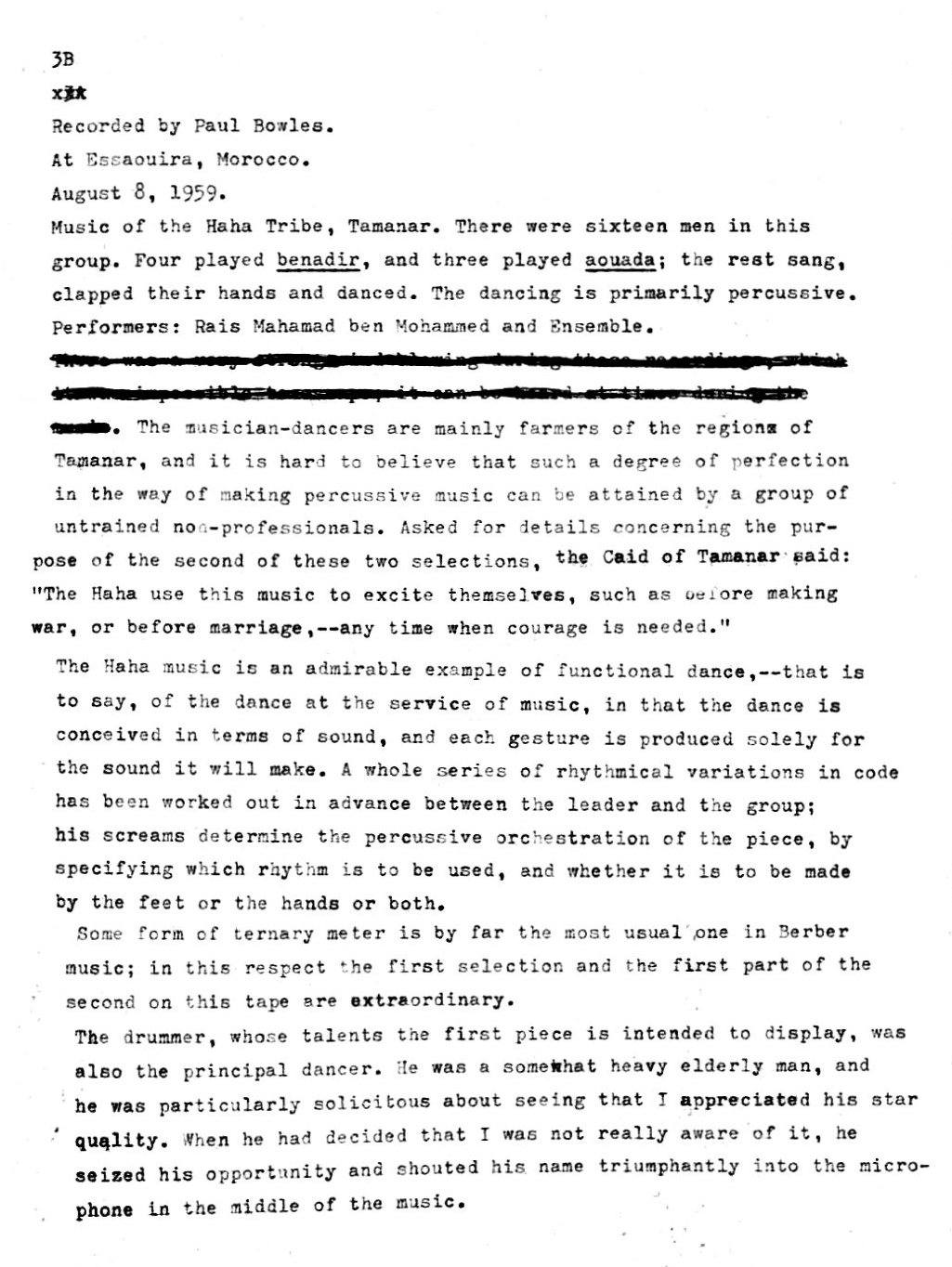

Morocco: Beneath The Sheltering Sky

Equipped with a Volkswagen Beetle, an Ampex 601 tape recorder the size of a suitcase and a trunk full of "piping hot Pepsi" Paul Bowles set out in 1959 to record as many hours of Moroccan folk music as possible. Accompanied by a Canadian expatriate and a Moroccan assistant they covered the entire coast from Tangier to Goulimine in the south, went over both the Rif and Atlas mountain range to the dune desert of Zagora and the border to Algeria.

During the four-month field project sponsored by the Library of Congress Bowles drove almost 40'000 km and captured vocal and instrumental music of various tribes and other indigenous populations at 23 locations throughout the country. The greatest difficulty turned out to be the government’s position that the region’s tribal culture was a hindrance to bigger dreams of development, and so Bowles found himself in a run against time, fearing his subject would be lost forever.

While he was best known as author of The Sheltering Sky, a 1949 novel about displaced Americans travelling the North African desert, Bowles was also a composer with ties to Aaron Copland and John Cage as well a creator of theatre music for Orson Welles, but "didn’t have much patience for scholarship, didn’t like music theory, didn’t like to operate by the rules," says ethnomusicologist Philip Schuyler and yet collecting the recordings re-issued by Dust-to-Digital "in almost every instance, Bowles had made the best choice, technically and musically."

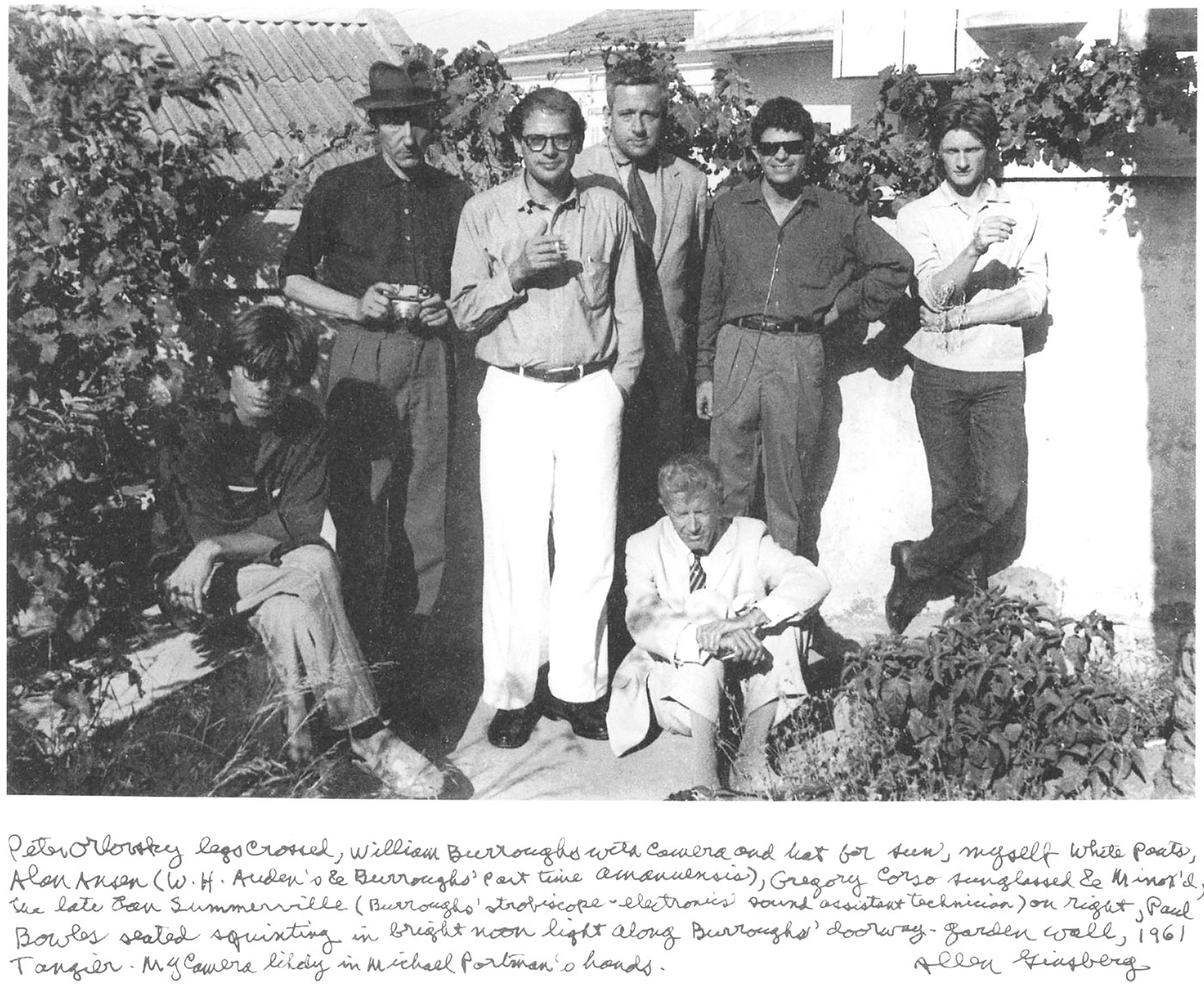

Husband of the brilliant writer Jane Bowles, he kept living in Tangier till his death, a city that became an outpost for leading lights of the Beat Generation, with Burroughs a mainstay as well as Brion Gysin, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and others.

While he was best known as author of The Sheltering Sky, a 1949 novel about displaced Americans travelling the North African desert, Bowles was also a composer with ties to Aaron Copland and John Cage as well a creator of theatre music for Orson Welles, but "didn’t have much patience for scholarship, didn’t like music theory, didn’t like to operate by the rules," says ethnomusicologist Philip Schuyler and yet collecting the recordings re-issued by Dust-to-Digital "in almost every instance, Bowles had made the best choice, technically and musically."

Husband of the brilliant writer Jane Bowles, he kept living in Tangier till his death, a city that became an outpost for leading lights of the Beat Generation, with Burroughs a mainstay as well as Brion Gysin, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and others.

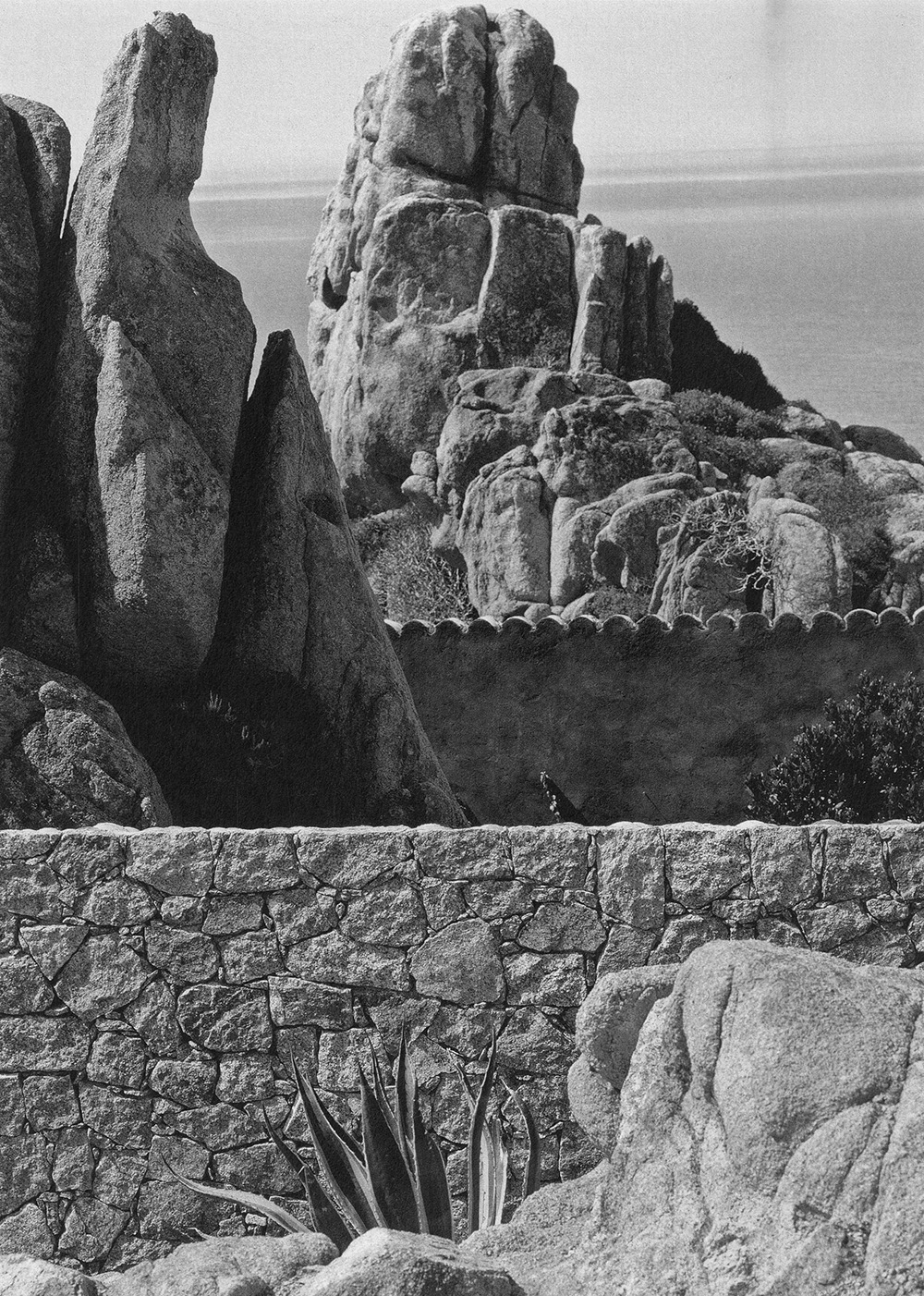

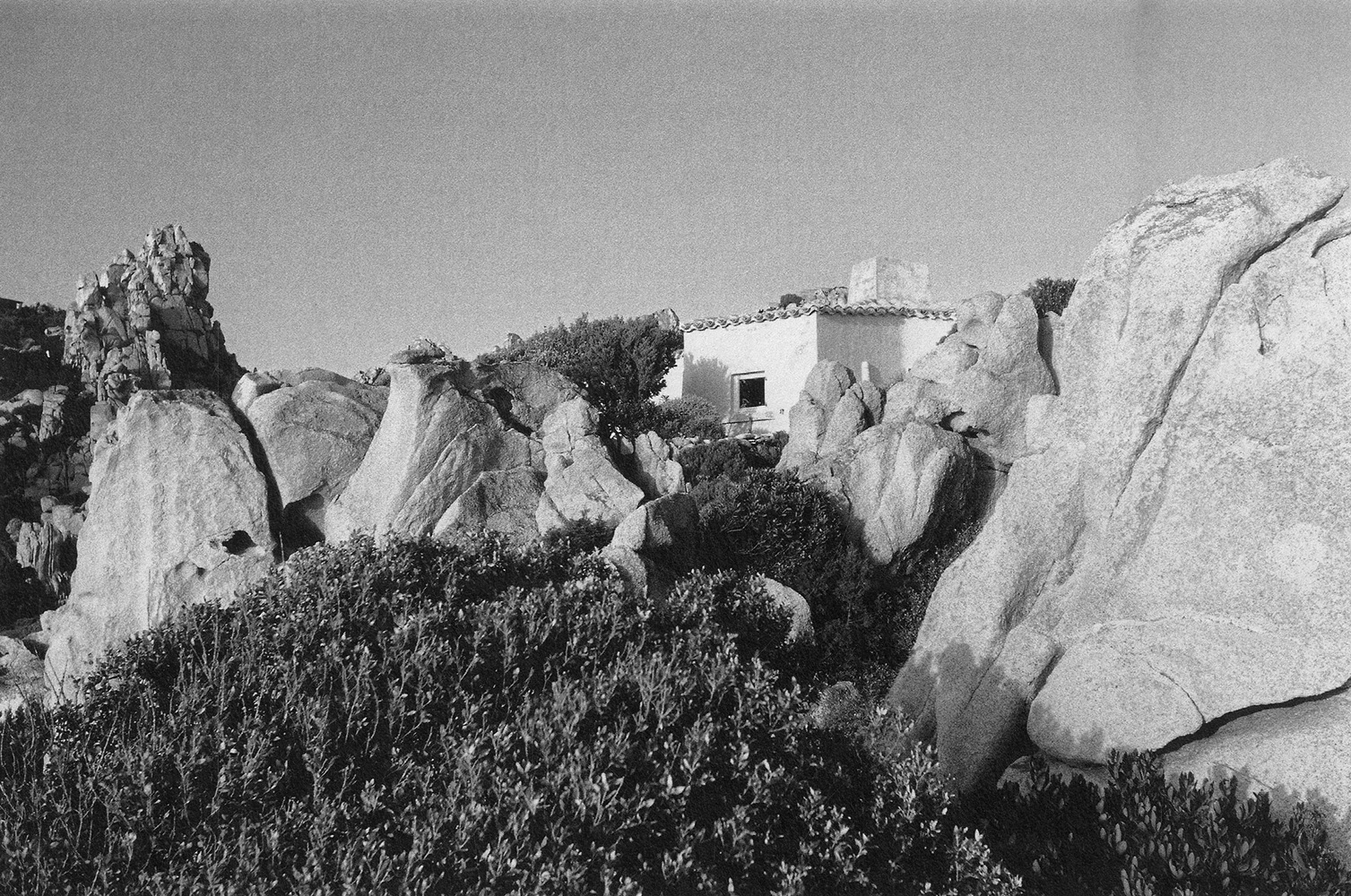

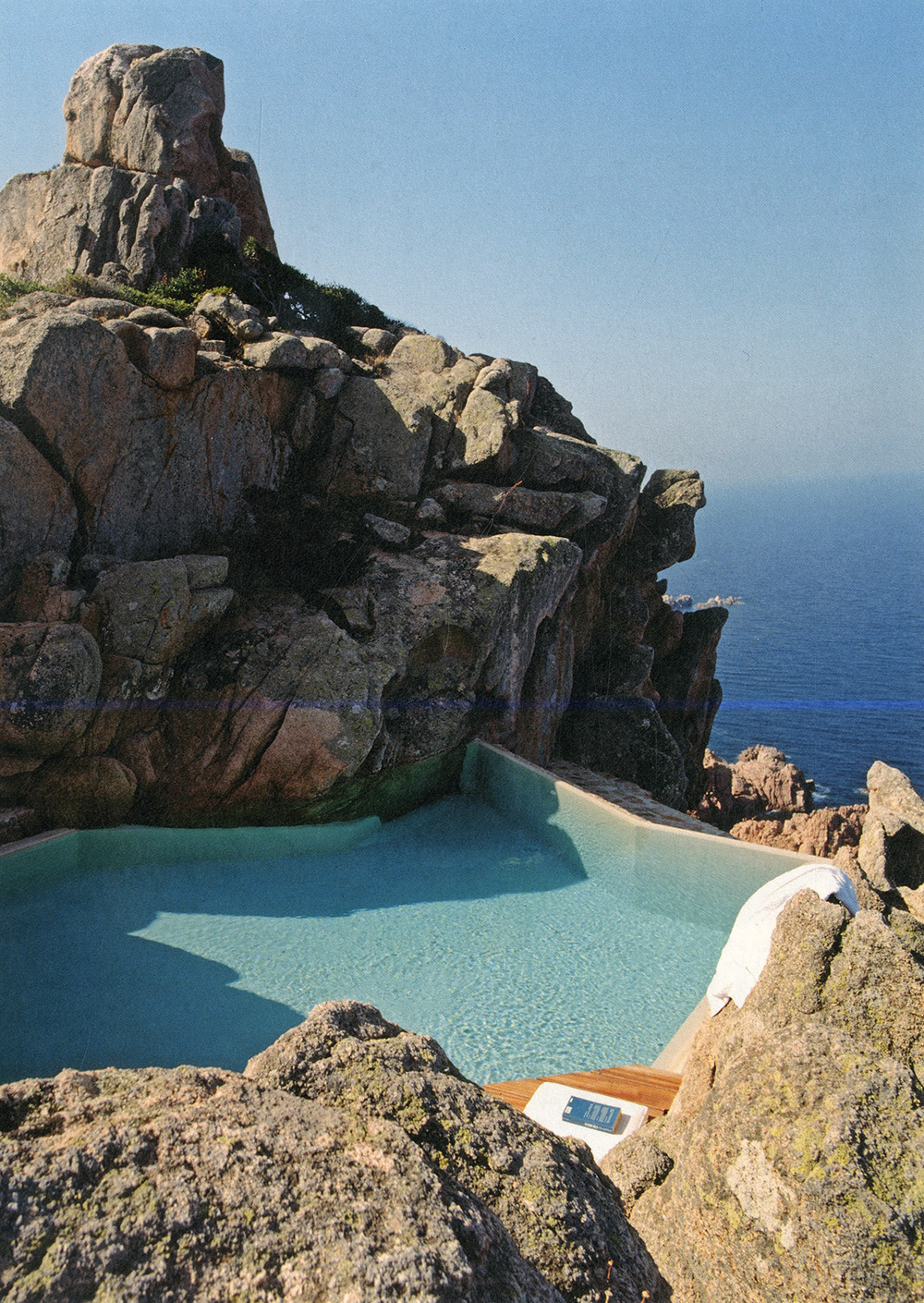

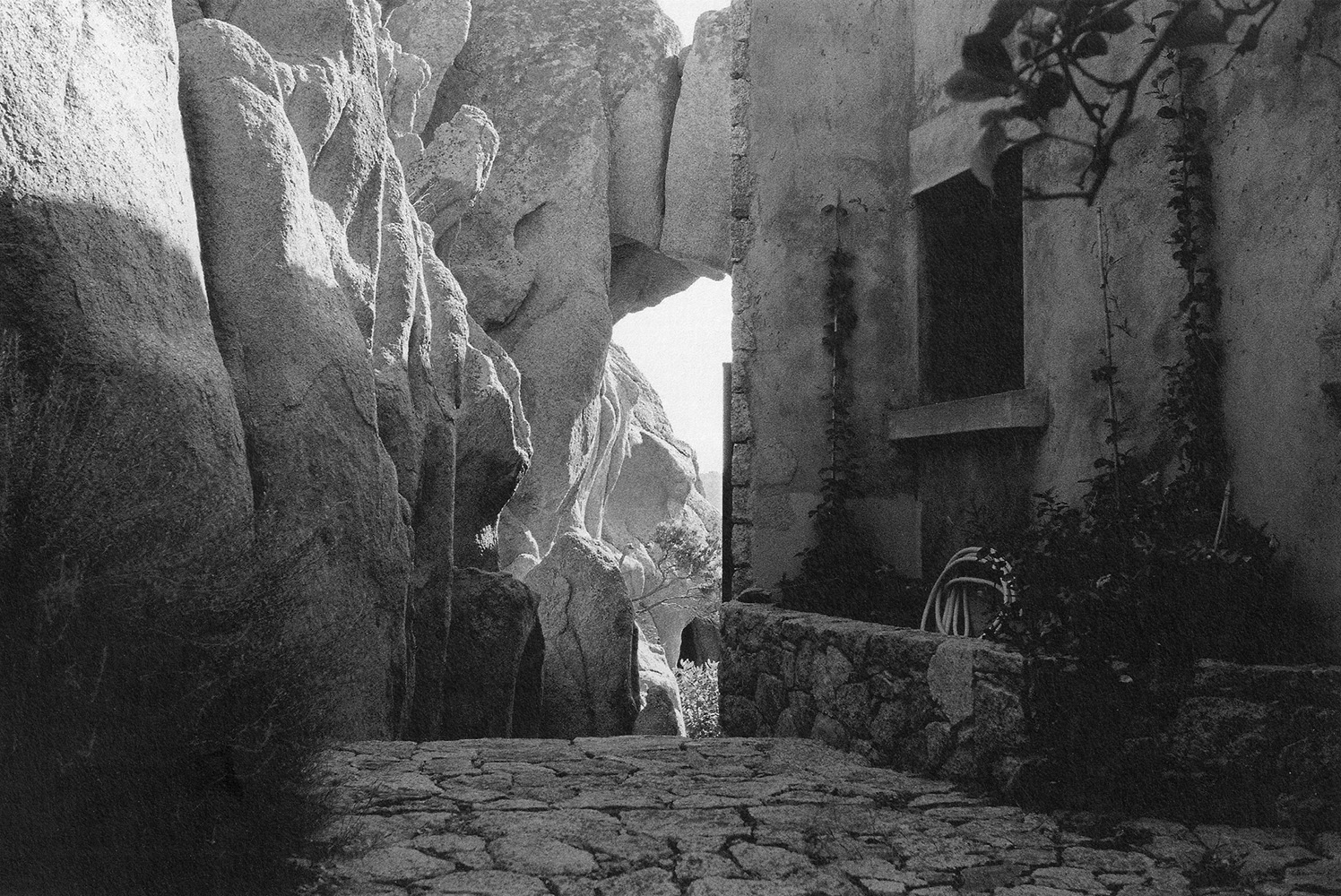

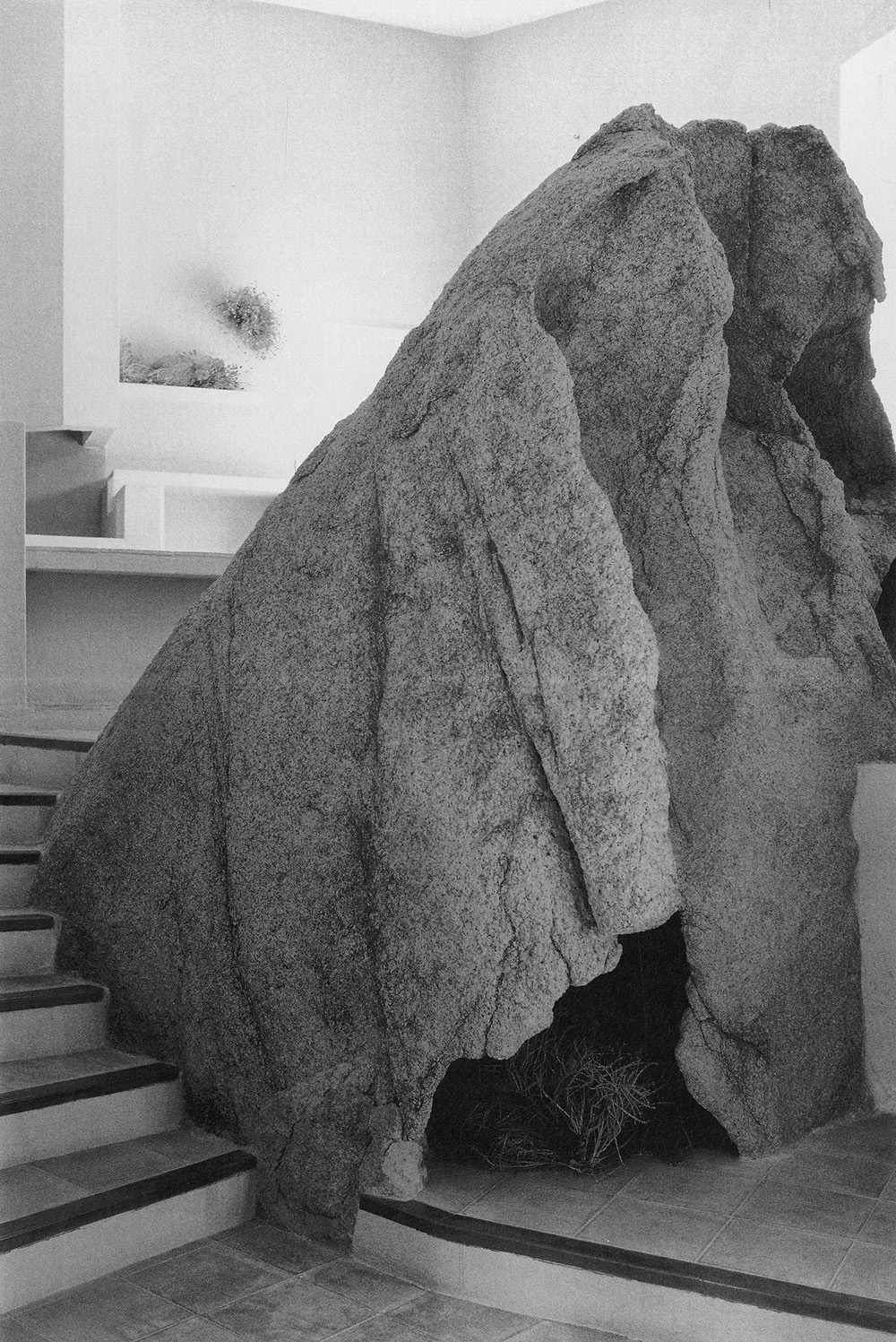

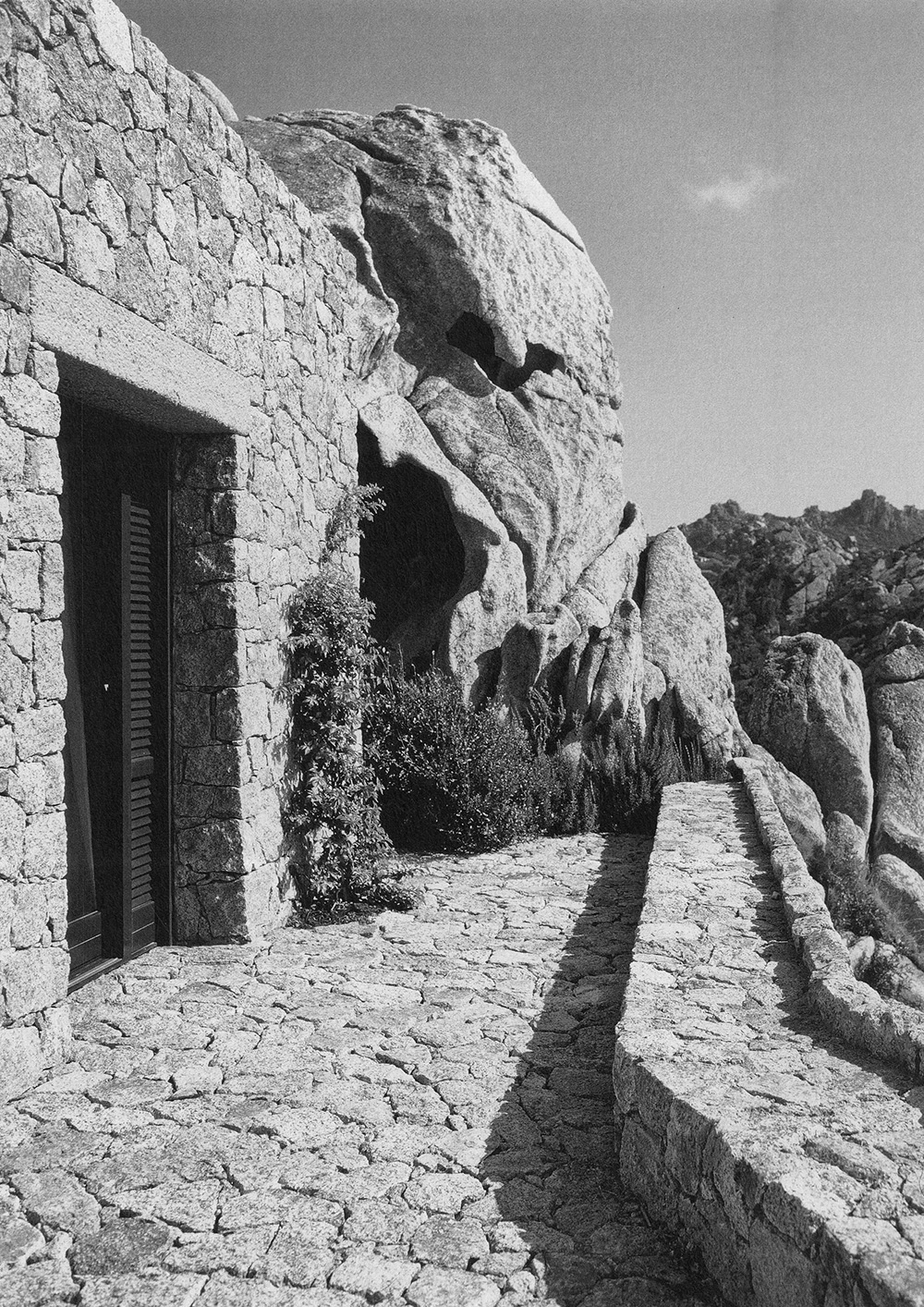

Sardinia: The

Inhabited Pathway

Architecture: Alberto Ponis

Photography: Gion von Albertini and Alberto Ponis

Publisher: Park Books

Alberto Ponis’ built work (about 300 buildings) is concentrated in the extraordinary rocky coastal landscape of northern Sardinia, where he has lived since the 1960’s. This series of houses, many of them holiday homes, combinine International Modernism, with a deep understanding of the local landscape and cultural condition – key examples of what Kenneth Frampton termed «critical regionalism». Given the work’s evident quality, the lack of attention is peculiar; its physical isolation might explain it, but then, Ponis’s architecture and personality don’t seek attention.

Born in Genoa in 1933, Ponis studied at the University of Florence, before going to London in 1960 to work at the offices of Goldfinger and then Lasdun. He returned to Italy in 1964, to set up practice in Palau, Sardinia where in 1970 he built Casa Hartley, one of his key early houses overlooking the sea, whose strict geometries of plan nevertheless merge into its bizarre rocky surroundings.

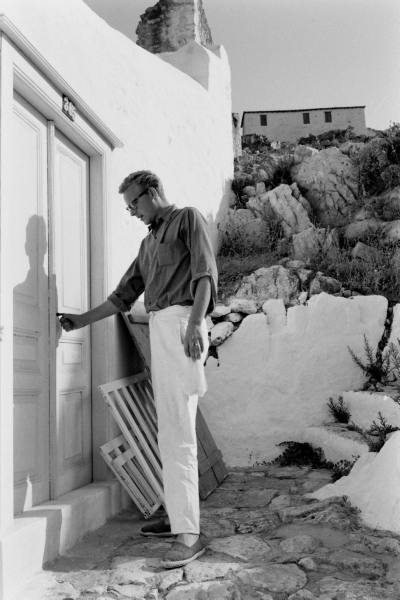

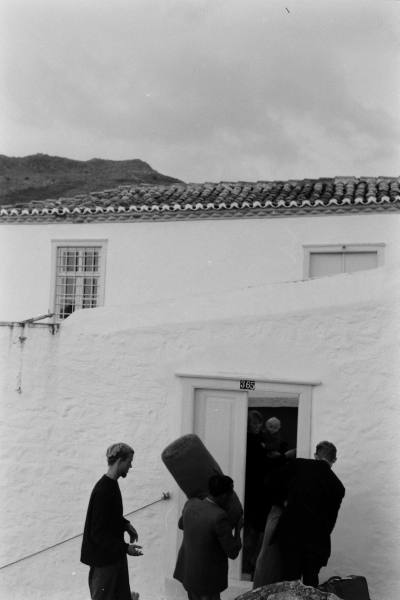

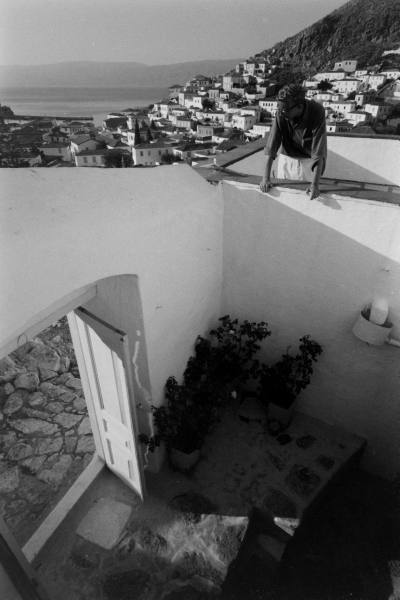

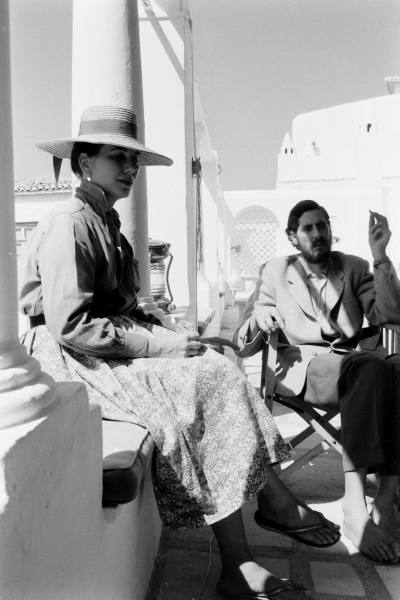

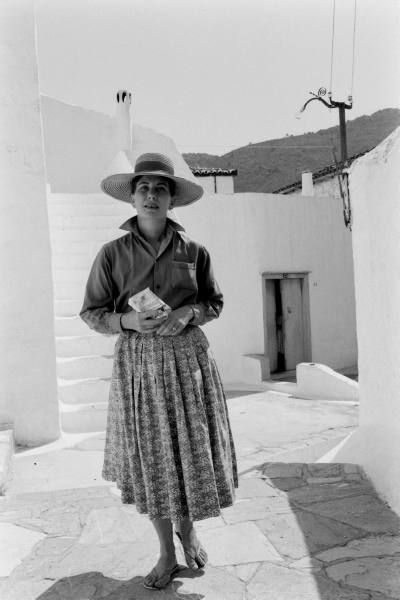

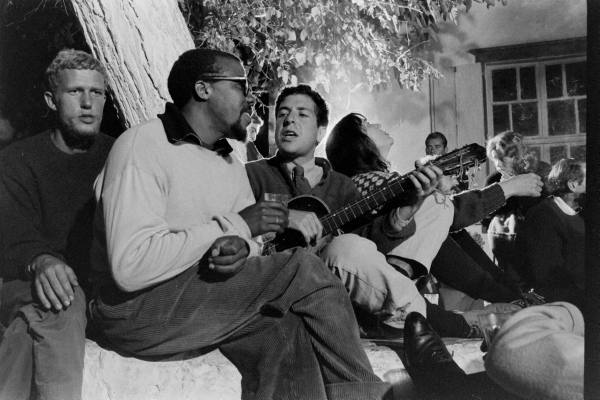

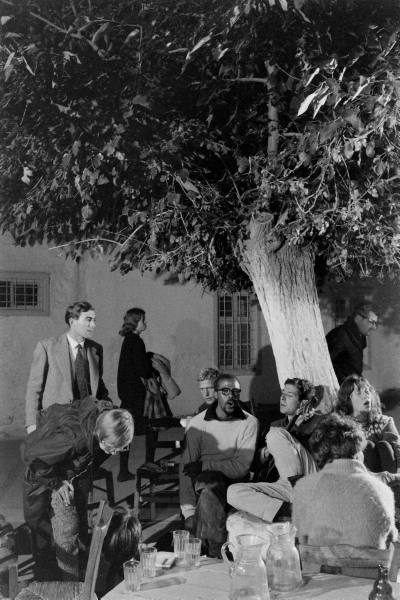

Hydra: Anything

that moves is white

Photography: James Burke (Hydra, 1960)

Poems: Leonard Cohen (Hydra, 1960-1967)

Poems: Leonard Cohen (Hydra, 1960-1967)

Anything that moves is white,

a gull, a wave, a sail,

and moves too purely to be aped.

Smash the pain.

Never pretend peace.

The consolamentum has not,

never will be kissed.

Pain cannot compromise this light.

Do violence to the pain,

ruin the easy vision,

the easy warning, water

for those who need to burn.

These are ruthless: rooster shriek,

bleached goat skull.

Scalpels grow with poppies

if you see them truly red.

1960

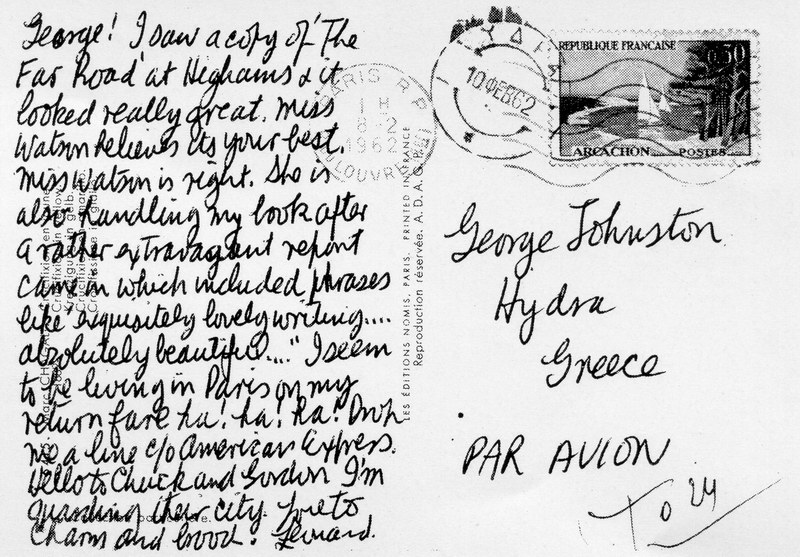

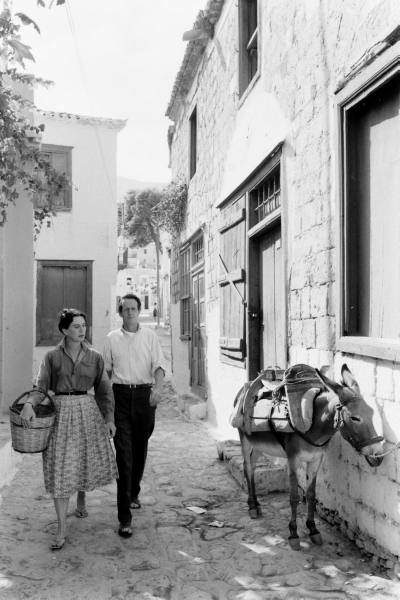

When Leonard Cohen arrived on Hydra in 1960 he quickly discovered a Bohemian community headed by the Australian writers George Johnston and Charmian Clift who settled there a few years earlier after they had given up their careers in journalism and escaped London’s high life for the vagaries of the literary life on a remote Greek island. Cohen later said: “The Johnstons were central figures. They were older. They were doing what we all wanted to do, which was to write and to make a living out of writing.

They were very wonderful, colorful, hospitable people.” During 1963, amid the partying and the drinking, George began his iconic novel “My Brother Jack”. Daily, George pounded at the typewriter with Charmian sitting next to him correcting the typescript and helping him to remember life and events in Melbourne. Their routine was taxing. Every morning they would write until midday and then go down to the Katsikas cafe on the waterfront for lunch and wait for the ferry from Piraeus that would bring the mail and new artists and writers looking for adventure.

There they would meet friends and George would regale them with stories about Australia and his adventures as a war correspondent. It was during one of these conversations in 1963 that George was discussing his latest book with Leonard, and said, “I just don’t know what to call it”.

“What’s it about?” Leonard asked. “My brother Jack,” George replied. Leonard said: “There you are.”

“What’s it about?” Leonard asked. “My brother Jack,” George replied. Leonard said: “There you are.”

The stony path coiled around me

and bound me to the night.

A boat hunted the edge of the sea

under a hissing light.

Something soft involved a net

and bled around a spear.

The blunt death, the cumulus jet

I spoke to you, I thought you near!

Or was the night so black

that something died alone?

A man with a glistening back

beat the food against a stone.

1963

and bound me to the night.

A boat hunted the edge of the sea

under a hissing light.

Something soft involved a net

and bled around a spear.

The blunt death, the cumulus jet

I spoke to you, I thought you near!

Or was the night so black

that something died alone?

A man with a glistening back

beat the food against a stone.

1963

They are still singing down at Dusko’s,

sitting under the ancient pine tree,

in the deep night of fixed and falling stars.

If you go to your window you can hear them.

It is the end of someone’s wedding,

or perhaps a boy is leaving on a boat in the morning.

There is a place for you at the table,

wine for you, and apples from the mainland,

a space in the songs for your voice.

Throw something on,

and whoever it is you must tell

that you are leaving,

tell them, or take them, but hurry:

they have sent for you

the call has come

they will not wait forever.

They are not even waiting now.

1967

sitting under the ancient pine tree,

in the deep night of fixed and falling stars.

If you go to your window you can hear them.

It is the end of someone’s wedding,

or perhaps a boy is leaving on a boat in the morning.

There is a place for you at the table,

wine for you, and apples from the mainland,

a space in the songs for your voice.

Throw something on,

and whoever it is you must tell

that you are leaving,

tell them, or take them, but hurry:

they have sent for you

the call has come

they will not wait forever.

They are not even waiting now.

1967

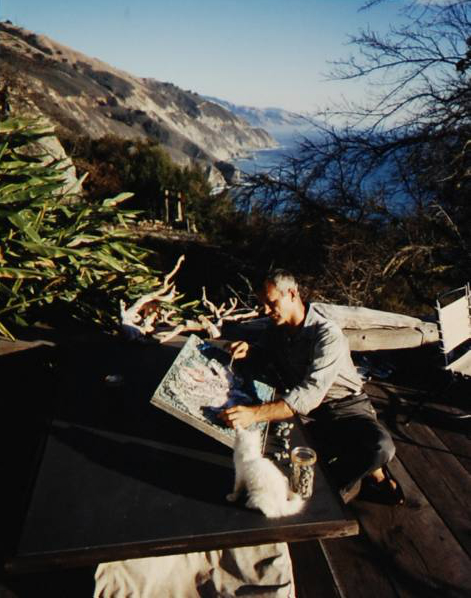

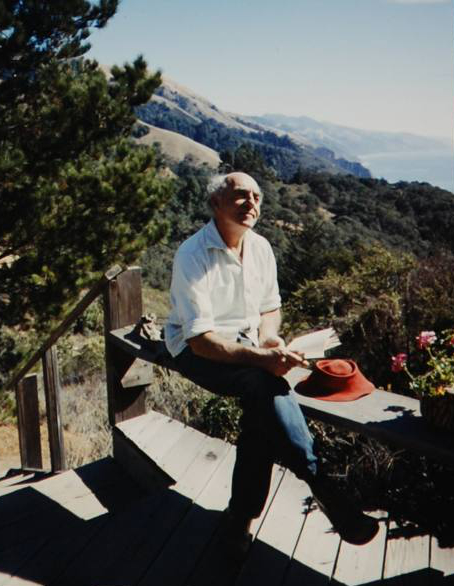

Big Sur: The Tropic Of Henry Miller

Text: Hunter S. Thompson (Rogue, 1961)

Photography: J R Eyerman (Life, 1960)

If half the stories about Big Sur were true the vibrations of all the orgies would have collapsed the entire Santa Lucia mountain range, making the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah seem like the work of a piker. And if justice were done, a whole army of tourists and curiosity-seekers would perish, too. It’s not likely to happen, however, because almost everything you hear about Big Sur is rumor, legend or an outright lie. This place is a myth-maker’s paradise, so vast and so varied and so beautiful that the imagination of the visitor is tempted to run wild at the sight of it.

In reality, Big Sur is very like Valhalla — a place that a lot of people have heard of, and that very few can tell you anything about. In New York you might hear it’s an art colony, in San Francisco they’ll tell you it’s a nudist colony, and when you finally roll into Big Sur with your eyes peeled for naked artists you are likely to be very disappointed.

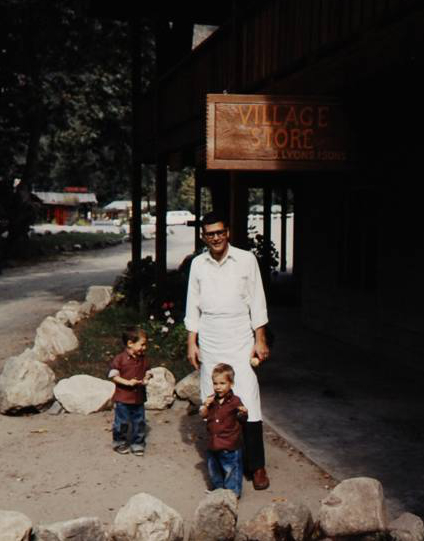

Every weekend Dick Hartford, owner of the local Village Store, is plagued by people looking for “sex orgies,” “wild drinking brawls,” or “the road to Henry Miller’s house” — as if once they found Miller everything else would be taken care of. Some of them will stay as long as a week, just wandering around, asking questions, forever popping up where you least expect them — finally wandering off, complaining bitterly that Big Sur is “nothing but a damn wilderness.”

Most of it is. The geographical boundaries of Big Sur are so vague that Lillian Bos Ross, one of the first writers to live here, once described it as “not a place at all, but a state of mind.” The Big Sur country is roughly eighty miles long and twenty wide, with a population of some three hundred souls spread out across the hills and along the coast. The “town” itself is nothing but a post office, village store, gas station, garage and restaurant, located a hundred and fifty miles south of San Francisco on California Highway One.

Time was when this place was as lonely and isolated as any spot in America. But no longer. Inevitably, Big Sur has been “discovered,” LIFE called it a “Rugged, Romantic World Apart,” and presented nine pages of pictures to prove it. After that there was no hope. Not that Henry Luce has anything against solitude — he just wants to tell his seven million readers about it. And on some weekends it seems like all seven million of them are right here, bubbling over with questions:

Every weekend Dick Hartford, owner of the local Village Store, is plagued by people looking for “sex orgies,” “wild drinking brawls,” or “the road to Henry Miller’s house” — as if once they found Miller everything else would be taken care of. Some of them will stay as long as a week, just wandering around, asking questions, forever popping up where you least expect them — finally wandering off, complaining bitterly that Big Sur is “nothing but a damn wilderness.”

Most of it is. The geographical boundaries of Big Sur are so vague that Lillian Bos Ross, one of the first writers to live here, once described it as “not a place at all, but a state of mind.” The Big Sur country is roughly eighty miles long and twenty wide, with a population of some three hundred souls spread out across the hills and along the coast. The “town” itself is nothing but a post office, village store, gas station, garage and restaurant, located a hundred and fifty miles south of San Francisco on California Highway One.

Time was when this place was as lonely and isolated as any spot in America. But no longer. Inevitably, Big Sur has been “discovered,” LIFE called it a “Rugged, Romantic World Apart,” and presented nine pages of pictures to prove it. After that there was no hope. Not that Henry Luce has anything against solitude — he just wants to tell his seven million readers about it. And on some weekends it seems like all seven million of them are right here, bubbling over with questions:

“Where’s the art colony, man? I’ve come all the way from Tennessee to join it.”

“Say, fella, where do I find this nudist colony?”

“Hello there. My wife and I want to rent a cheap ten-room house for weekends, Could you tell me where to look?”

Or the one that drove Miller half-crazy: “Ah ha! So you’re Henry Miller! Well my name is Claude Fink and I’ve come to join the cult of sex and anarchy.”

Most of the people who’ve heard of Big Sur know nothing about it except that Miller lives here. There is no doubt in their minds that any place Miller lives is bound to be some sort of sexual mecca. Ironically enough, Miller came here looking for peace and solitude. When he arrived in 1946 he was relatively unknown. His major works (Tropics of Cancer & Capricorn, The Rosy Crucifixion, and Black Spring) were banned in this country. And all but the first of these still are. In Europe, where he had lived since the early Thirties, he had a reputation as one of the few honest and uncompromising American writers. But when the Nazis over-ran Paris his income was cut off and he came back to the United States.

His contempt for this country was manifest in everything he wrote, and his vision of America’s future was a hairy thing, at best. In “The World of Sex,” a banned and little-known book he wrote in 1940, he put it like this:

“What will happen when this world of neuters who make up the great bulk of the population collapses is this — they will discover sex. In the period of darkness which will ensue they will lie up in the dark like snakes or toads and chew each other alive during the endless fornication carnival.”

These are the words that came back to haunt him when he moved to Big Sur. No sooner had he settled here, hoping to separate himself from what he called “The Air-Conditioned Night-mare,” than thousands of people sought him out.

“Say, fella, where do I find this nudist colony?”

“Hello there. My wife and I want to rent a cheap ten-room house for weekends, Could you tell me where to look?”

Or the one that drove Miller half-crazy: “Ah ha! So you’re Henry Miller! Well my name is Claude Fink and I’ve come to join the cult of sex and anarchy.”

Most of the people who’ve heard of Big Sur know nothing about it except that Miller lives here. There is no doubt in their minds that any place Miller lives is bound to be some sort of sexual mecca. Ironically enough, Miller came here looking for peace and solitude. When he arrived in 1946 he was relatively unknown. His major works (Tropics of Cancer & Capricorn, The Rosy Crucifixion, and Black Spring) were banned in this country. And all but the first of these still are. In Europe, where he had lived since the early Thirties, he had a reputation as one of the few honest and uncompromising American writers. But when the Nazis over-ran Paris his income was cut off and he came back to the United States.

His contempt for this country was manifest in everything he wrote, and his vision of America’s future was a hairy thing, at best. In “The World of Sex,” a banned and little-known book he wrote in 1940, he put it like this:

“What will happen when this world of neuters who make up the great bulk of the population collapses is this — they will discover sex. In the period of darkness which will ensue they will lie up in the dark like snakes or toads and chew each other alive during the endless fornication carnival.”

These are the words that came back to haunt him when he moved to Big Sur. No sooner had he settled here, hoping to separate himself from what he called “The Air-Conditioned Night-mare,” than thousands of people sought him out.

When all Miller wanted was a little privacy, they struggled up the steep dirt road to his house on Partington Ridge; if there was a fornication carnival going on up there, they were damn well going to be in on it. At times it seemed like half the population of Greenwich Village was camping on his lawn.

Miller did his best to stem the tide, but it was no use. As his fame spread, his volume of visitors mounted steadily. Many of them had not even read his books. They weren’t interested in literature, they wanted orgies. And they were shocked to find him a quiet, fastidious and very moral man, instead of the raving sexual beast they’d heard stories about. When no orgies materialized cultists drifted on to Los Angeles or San Francisco, or stayed in Big Sur, trying to drum up orgies of their own. Some of them lived in hollow trees, others found abandoned shacks, and a few simply roamed the hills with sleeping bags, living on nuts, berries and wild mustard greens. Miller tried to drive his visitors away but nothing worked. They finally overwhelmed him, and in the process they put Big Sur squarely on the map of national curiosities. Today they are still coming, even though Miller has packed his bags and fled to Europe for what may be a permanent vacation.

The special irony of all this is that Miller has written more about Big Sur — and praised it more — than any other writer in the world. In 1946 he wrote an essay called “This Is My Answer,” which eventually appeared in his book, “Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch,” published in 1958, long after the first invasion.

“Peace and solitude!” he says. “I have had a taste of it even in America. Mornings on Partington Ridge I would often go to the cabin door on rising, look out over the rolling velvety hills, filled with such contentment, such gratitude, that instinctively my hand went up in a benediction.”

Miller did his best to stem the tide, but it was no use. As his fame spread, his volume of visitors mounted steadily. Many of them had not even read his books. They weren’t interested in literature, they wanted orgies. And they were shocked to find him a quiet, fastidious and very moral man, instead of the raving sexual beast they’d heard stories about. When no orgies materialized cultists drifted on to Los Angeles or San Francisco, or stayed in Big Sur, trying to drum up orgies of their own. Some of them lived in hollow trees, others found abandoned shacks, and a few simply roamed the hills with sleeping bags, living on nuts, berries and wild mustard greens. Miller tried to drive his visitors away but nothing worked. They finally overwhelmed him, and in the process they put Big Sur squarely on the map of national curiosities. Today they are still coming, even though Miller has packed his bags and fled to Europe for what may be a permanent vacation.

The special irony of all this is that Miller has written more about Big Sur — and praised it more — than any other writer in the world. In 1946 he wrote an essay called “This Is My Answer,” which eventually appeared in his book, “Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch,” published in 1958, long after the first invasion.

“Peace and solitude!” he says. “I have had a taste of it even in America. Mornings on Partington Ridge I would often go to the cabin door on rising, look out over the rolling velvety hills, filled with such contentment, such gratitude, that instinctively my hand went up in a benediction.”

The steamroller of progress has made slow headway in Big Sur. In some spots, in fact, it has bogged down altogether.

To read a New York Times in Big Sur can be a traumatic experience. After living here a few months you find it increasingly difficult to take that mass of threatening, complicated information very seriously. There are people here without the vaguest idea of what is happening in the rest of the world. They haven’t read a newspaper in years, don’t listen to the radio, and see a television set perhaps once a month when they go into town.

Here they didn’t even have electricity until 1947, or telephones until 1958. Compared to the rest of California, Big Sur seems brutally primitive. No subdivisions mark these rugged hills, no supermarkets, no billboards, no crowded commercial wharfs jutting into the sea. In the entire eighty mile stretch of coastline there are only five gas stations and two grocery stores. A fifty mile stretch of the coast is still without electricity. The people who live there — and some of them own whole mountains of virgin land — are still using gas lanterns and Coleman stoves.

To read a New York Times in Big Sur can be a traumatic experience. After living here a few months you find it increasingly difficult to take that mass of threatening, complicated information very seriously. There are people here without the vaguest idea of what is happening in the rest of the world. They haven’t read a newspaper in years, don’t listen to the radio, and see a television set perhaps once a month when they go into town.

Here they didn’t even have electricity until 1947, or telephones until 1958. Compared to the rest of California, Big Sur seems brutally primitive. No subdivisions mark these rugged hills, no supermarkets, no billboards, no crowded commercial wharfs jutting into the sea. In the entire eighty mile stretch of coastline there are only five gas stations and two grocery stores. A fifty mile stretch of the coast is still without electricity. The people who live there — and some of them own whole mountains of virgin land — are still using gas lanterns and Coleman stoves.

It is still possible to roam these hills for days at a time without seeing anything but deer, wolves, mountain lions and wild boar. Pads of Big Sur remain as wild and lonely as they were when Jack London used to come down on horseback from San Francisco. The house he stayed in is still here, high on a ridge a few miles south of the post office. With a little luck a man can still come here and live entirely by himself, but most of the people who arrive don’t have that in mind. These are the transients — the “orphans” and the “weekend ramblers.” The orphans are the spiritually homeless, the disinherited souls of a complex and nerve-wracked society. They can be lawyers, laborers, beatniks or wealthy dilettantes, but they are all looking for a place where they can settle and “feel at home.” Some of them stay, finding in Big Sur the freedom and relaxation they couldn’t find anywhere else. But most of them move on, finding it “too dull” or “too lonely” for their tastes.

The highway alone is enough to give a man pause. It climbs and twists along the cliffs like a huge asphalt roller-coaster; in some spots you can look eight-hundred feet straight down to the booming surf.

The highway alone is enough to give a man pause. It climbs and twists along the cliffs like a huge asphalt roller-coaster; in some spots you can look eight-hundred feet straight down to the booming surf.

The coast from Carmel to San Simeon, with the green slopes of the Santa Lucia mountains plunging down to the sea, is nothing short of awesome. Nepenthe, open from April to November, is one of the most beautiful restaurants anywhere in America; and Chaco, the lecherous old Tsarist writer who, in his words, “hustles liquor” on the Nepenthe terrace, is as colorful a character as a man could hope to meet.

There are plenty of artists here, and most of them exhibit at the Coast Gallery, about halfway between Nepenthe and Hot Springs. Like artists everywhere, many do odd jobs to keep eating and pay the rent. Others, like Bennett Bradbury, drive new Cadillac convertibles and live in “fashionable” Coastlands or Partington Ridge.

On any given day you might walk into the Village Store and find three Frenchmen and two bearded Greeks arguing the fine points of Dada poetry — and on the day after that you’ll find nobody there but a local rancher, muttering to himself about the dangers of hoof-and-mouth disease.

There are plenty of artists here, and most of them exhibit at the Coast Gallery, about halfway between Nepenthe and Hot Springs. Like artists everywhere, many do odd jobs to keep eating and pay the rent. Others, like Bennett Bradbury, drive new Cadillac convertibles and live in “fashionable” Coastlands or Partington Ridge.

On any given day you might walk into the Village Store and find three Frenchmen and two bearded Greeks arguing the fine points of Dada poetry — and on the day after that you’ll find nobody there but a local rancher, muttering to himself about the dangers of hoof-and-mouth disease.

The local poets outnumber the wild boars, but Eric Barker is the only “name”, and he looks too much like a farmer to cause any stir among the tourists. For that matter almost everyone in Big Sur looks like either a farmer or a woodsy poet. People are always taking Emil White, publisher of the Big Sur Guide, for a hermit or a sex fiend; and Helmuth Deetjen, owner of the Big Sur Inn, looks more like a junkie than a lot of real hopheads. If you saw Nicholas Roosevelt, of the Oyster Bay Roosevelts, walking along the highway you might expect him to flag you down, wipe your windshield with an old handkerchief, and ask for a quarter, but he won’t.

To see Big Sur is one thing, and to live here is quite another. The little man who comes down from the city to “get away from it all” — runs amok on wine two weeks later because there is nobody to talk to and the silence is driving him crazy. Big Sur is full of loneliness.

Today the population of Big Sur is smaller than it was in 1900, and just about the same as it was in 1945. Hundreds of people have tried to settle here since the end of the war, and hundreds have failed. Those who come from the cities, hoping to join a merry band of hard-drinking exiles from an over-organized society, are soon disappointed. The exiles are hard to locate, and even harder to drink with. Soon the silence becomes ominous; the pounding sea is too hostile and the nights are full of strange sounds. On some days the only thing to do, besides eat and sleep, is walk up to your mailbox and meet the postman, who drives down from Monterey six days a week in a Volkswagen bus, bringing news-papers, groceries and beer along with your mail.

If you come here looking for something to join or to lean on for support, you are in for a bad time.

In his book on Big Sur, Miller describes the people he found here when he came. Some of them, depressed by the influx of tourists, have left for other, more isolated spots — Mexico, the Pacific Northwest, or the Greek Islands. But many are still living here the same way they were before.

To see Big Sur is one thing, and to live here is quite another. The little man who comes down from the city to “get away from it all” — runs amok on wine two weeks later because there is nobody to talk to and the silence is driving him crazy. Big Sur is full of loneliness.

Today the population of Big Sur is smaller than it was in 1900, and just about the same as it was in 1945. Hundreds of people have tried to settle here since the end of the war, and hundreds have failed. Those who come from the cities, hoping to join a merry band of hard-drinking exiles from an over-organized society, are soon disappointed. The exiles are hard to locate, and even harder to drink with. Soon the silence becomes ominous; the pounding sea is too hostile and the nights are full of strange sounds. On some days the only thing to do, besides eat and sleep, is walk up to your mailbox and meet the postman, who drives down from Monterey six days a week in a Volkswagen bus, bringing news-papers, groceries and beer along with your mail.

If you come here looking for something to join or to lean on for support, you are in for a bad time.

In his book on Big Sur, Miller describes the people he found here when he came. Some of them, depressed by the influx of tourists, have left for other, more isolated spots — Mexico, the Pacific Northwest, or the Greek Islands. But many are still living here the same way they were before.

“These young men, usually in their late twenties or early thirties . . are not concerned with undermining a vicious system, but with leading their own lives — on the fringe of society. It is only natural to find them gravitating towards such places as Big Sur.”

These are the expatriates, the ones who have come from all over the world to make a stab at The Good Life. But there are others, too. Some are ranchers whose families have lived here for generations. Others are out-and-out bastards, who live in isolation because they can’t live anywhere else. And a few are genuine deviates, who live here because nobody cares what they do as long as they keep to themselves.

In some respects Big Sur is closer to New York and Paris than to Monterey and San Francisco. To the writers and photographers who live here just a few months of the year, New York is the axis of the earth — where the publishers are, where assignments originate and where all the checks are signed. And once the checks are cashed, Paris is the next stop. After that it’s keep moving until the money runs out, then back to Big Sur. In their minds, San Francisco is a bar, Monterey is a grocery store, and L.A. is a circus a few hundred miles down the road.

Others, primarily the painters and sculptors, look north to Carmel, with its many art galleries, craft-centers and wallet-heavy tourists.

Visitors in Big Sur — those who are actually invited — are more likely to be artists, foreign journalists or world travelers than, ordinary vacationers. There are no hotels here, the motels are small and devoid of entertainment, and the only night-life revolves around Nepenthe, which is close-d five months of the year.

This is the way life goes in Big Sur: waiting for the mail, watching the sealions in the surf or the dim lights of a ship far out at sea, sitting in the tubs at Hot Springs, once in a while a bit of drink — and, most of the time, working at whatever it is that you came here to work on whether it be painting, writing, gardening or the simple art of living your own life.

These are the expatriates, the ones who have come from all over the world to make a stab at The Good Life. But there are others, too. Some are ranchers whose families have lived here for generations. Others are out-and-out bastards, who live in isolation because they can’t live anywhere else. And a few are genuine deviates, who live here because nobody cares what they do as long as they keep to themselves.

In some respects Big Sur is closer to New York and Paris than to Monterey and San Francisco. To the writers and photographers who live here just a few months of the year, New York is the axis of the earth — where the publishers are, where assignments originate and where all the checks are signed. And once the checks are cashed, Paris is the next stop. After that it’s keep moving until the money runs out, then back to Big Sur. In their minds, San Francisco is a bar, Monterey is a grocery store, and L.A. is a circus a few hundred miles down the road.

Others, primarily the painters and sculptors, look north to Carmel, with its many art galleries, craft-centers and wallet-heavy tourists.

Visitors in Big Sur — those who are actually invited — are more likely to be artists, foreign journalists or world travelers than, ordinary vacationers. There are no hotels here, the motels are small and devoid of entertainment, and the only night-life revolves around Nepenthe, which is close-d five months of the year.

This is the way life goes in Big Sur: waiting for the mail, watching the sealions in the surf or the dim lights of a ship far out at sea, sitting in the tubs at Hot Springs, once in a while a bit of drink — and, most of the time, working at whatever it is that you came here to work on whether it be painting, writing, gardening or the simple art of living your own life.

What — and whom — you find here depends largely on where you look. Partington Ridge, for instance, is Big Sur’s answer to Park Avenue. Nicholas Roosevelt lives there; so does Sam Hopkins, of the Top Of The Mark (Hopkins Hotel) clan. Visiting luminaries are usually quartered on Partington, and when they sit down to eat they are not likely to be served wild mustard greens.

On the Murphy property, including Hot Springs, the combined rental on nine dwellings is $176 a month. This place is a real menagerie, flavored with everything from bestiality to touch football. The barn rents for $15, the farmhouse for $4O, and a shack in the canyon goes for $5. The list of tenants reads something like this: one photographer, one bartender, one publisher, one carpenter, one writer, one fugitive, one metal sculptor, one Zen Buddhist, one physical culturist, one lawyer, and three people who simply defy description — sexually, socially or any other way. There are two legitimate wives on the property; the other females are either mistresses, “companions,” or hopeless losers. Until recently the shining light of this community was Dennis Murphy, the novelist, whose grandmother owns the whole shebang. But when his book, “The Sergeant,” became a best-seller, he was hounded by people who would drive hundreds of miles to jabber at him and drink his liquor. After a few months of this he moved up the coast to Monterey.

Old Mrs. Murphy lives across the mountains in Salinas, and, luckily, gets to Big Sur only two or three times a year. Her husband, the late Dr. Murphy, conceived of this place as a great health spa, a virtual bastion of decency and clean living.

Miller, in one of his rosier moods, said this coast would one day be the Riviera of America. Maybe so, but it will take quite a while. And in the meantime it is one of the finest places in the world to sit naked in the sun and read the New York Times. ●

On the Murphy property, including Hot Springs, the combined rental on nine dwellings is $176 a month. This place is a real menagerie, flavored with everything from bestiality to touch football. The barn rents for $15, the farmhouse for $4O, and a shack in the canyon goes for $5. The list of tenants reads something like this: one photographer, one bartender, one publisher, one carpenter, one writer, one fugitive, one metal sculptor, one Zen Buddhist, one physical culturist, one lawyer, and three people who simply defy description — sexually, socially or any other way. There are two legitimate wives on the property; the other females are either mistresses, “companions,” or hopeless losers. Until recently the shining light of this community was Dennis Murphy, the novelist, whose grandmother owns the whole shebang. But when his book, “The Sergeant,” became a best-seller, he was hounded by people who would drive hundreds of miles to jabber at him and drink his liquor. After a few months of this he moved up the coast to Monterey.

Old Mrs. Murphy lives across the mountains in Salinas, and, luckily, gets to Big Sur only two or three times a year. Her husband, the late Dr. Murphy, conceived of this place as a great health spa, a virtual bastion of decency and clean living.

Miller, in one of his rosier moods, said this coast would one day be the Riviera of America. Maybe so, but it will take quite a while. And in the meantime it is one of the finest places in the world to sit naked in the sun and read the New York Times. ●