Big Sur: The Tropic Of Henry Miller

Text: Hunter S. Thompson (Rogue, 1961)

Photography: J R Eyerman (Life, 1960)

If half the stories about Big Sur were true the vibrations of all the orgies would have collapsed the entire Santa Lucia mountain range, making the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah seem like the work of a piker. And if justice were done, a whole army of tourists and curiosity-seekers would perish, too. It’s not likely to happen, however, because almost everything you hear about Big Sur is rumor, legend or an outright lie. This place is a myth-maker’s paradise, so vast and so varied and so beautiful that the imagination of the visitor is tempted to run wild at the sight of it.

In reality, Big Sur is very like Valhalla — a place that a lot of people have heard of, and that very few can tell you anything about. In New York you might hear it’s an art colony, in San Francisco they’ll tell you it’s a nudist colony, and when you finally roll into Big Sur with your eyes peeled for naked artists you are likely to be very disappointed.

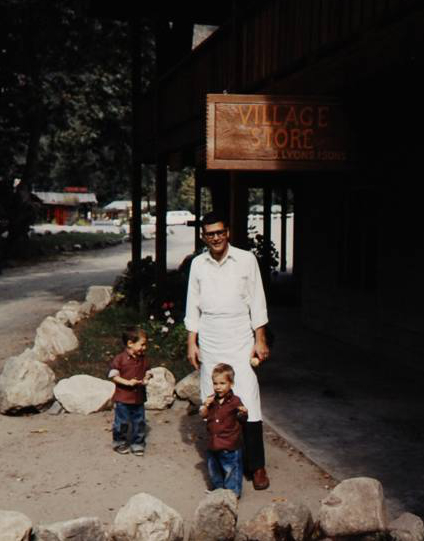

Every weekend Dick Hartford, owner of the local Village Store, is plagued by people looking for “sex orgies,” “wild drinking brawls,” or “the road to Henry Miller’s house” — as if once they found Miller everything else would be taken care of. Some of them will stay as long as a week, just wandering around, asking questions, forever popping up where you least expect them — finally wandering off, complaining bitterly that Big Sur is “nothing but a damn wilderness.”

Most of it is. The geographical boundaries of Big Sur are so vague that Lillian Bos Ross, one of the first writers to live here, once described it as “not a place at all, but a state of mind.” The Big Sur country is roughly eighty miles long and twenty wide, with a population of some three hundred souls spread out across the hills and along the coast. The “town” itself is nothing but a post office, village store, gas station, garage and restaurant, located a hundred and fifty miles south of San Francisco on California Highway One.

Time was when this place was as lonely and isolated as any spot in America. But no longer. Inevitably, Big Sur has been “discovered,” LIFE called it a “Rugged, Romantic World Apart,” and presented nine pages of pictures to prove it. After that there was no hope. Not that Henry Luce has anything against solitude — he just wants to tell his seven million readers about it. And on some weekends it seems like all seven million of them are right here, bubbling over with questions:

Every weekend Dick Hartford, owner of the local Village Store, is plagued by people looking for “sex orgies,” “wild drinking brawls,” or “the road to Henry Miller’s house” — as if once they found Miller everything else would be taken care of. Some of them will stay as long as a week, just wandering around, asking questions, forever popping up where you least expect them — finally wandering off, complaining bitterly that Big Sur is “nothing but a damn wilderness.”

Most of it is. The geographical boundaries of Big Sur are so vague that Lillian Bos Ross, one of the first writers to live here, once described it as “not a place at all, but a state of mind.” The Big Sur country is roughly eighty miles long and twenty wide, with a population of some three hundred souls spread out across the hills and along the coast. The “town” itself is nothing but a post office, village store, gas station, garage and restaurant, located a hundred and fifty miles south of San Francisco on California Highway One.

Time was when this place was as lonely and isolated as any spot in America. But no longer. Inevitably, Big Sur has been “discovered,” LIFE called it a “Rugged, Romantic World Apart,” and presented nine pages of pictures to prove it. After that there was no hope. Not that Henry Luce has anything against solitude — he just wants to tell his seven million readers about it. And on some weekends it seems like all seven million of them are right here, bubbling over with questions:

“Where’s the art colony, man? I’ve come all the way from Tennessee to join it.”

“Say, fella, where do I find this nudist colony?”

“Hello there. My wife and I want to rent a cheap ten-room house for weekends, Could you tell me where to look?”

Or the one that drove Miller half-crazy: “Ah ha! So you’re Henry Miller! Well my name is Claude Fink and I’ve come to join the cult of sex and anarchy.”

Most of the people who’ve heard of Big Sur know nothing about it except that Miller lives here. There is no doubt in their minds that any place Miller lives is bound to be some sort of sexual mecca. Ironically enough, Miller came here looking for peace and solitude. When he arrived in 1946 he was relatively unknown. His major works (Tropics of Cancer & Capricorn, The Rosy Crucifixion, and Black Spring) were banned in this country. And all but the first of these still are. In Europe, where he had lived since the early Thirties, he had a reputation as one of the few honest and uncompromising American writers. But when the Nazis over-ran Paris his income was cut off and he came back to the United States.

His contempt for this country was manifest in everything he wrote, and his vision of America’s future was a hairy thing, at best. In “The World of Sex,” a banned and little-known book he wrote in 1940, he put it like this:

“What will happen when this world of neuters who make up the great bulk of the population collapses is this — they will discover sex. In the period of darkness which will ensue they will lie up in the dark like snakes or toads and chew each other alive during the endless fornication carnival.”

These are the words that came back to haunt him when he moved to Big Sur. No sooner had he settled here, hoping to separate himself from what he called “The Air-Conditioned Night-mare,” than thousands of people sought him out.

“Say, fella, where do I find this nudist colony?”

“Hello there. My wife and I want to rent a cheap ten-room house for weekends, Could you tell me where to look?”

Or the one that drove Miller half-crazy: “Ah ha! So you’re Henry Miller! Well my name is Claude Fink and I’ve come to join the cult of sex and anarchy.”

Most of the people who’ve heard of Big Sur know nothing about it except that Miller lives here. There is no doubt in their minds that any place Miller lives is bound to be some sort of sexual mecca. Ironically enough, Miller came here looking for peace and solitude. When he arrived in 1946 he was relatively unknown. His major works (Tropics of Cancer & Capricorn, The Rosy Crucifixion, and Black Spring) were banned in this country. And all but the first of these still are. In Europe, where he had lived since the early Thirties, he had a reputation as one of the few honest and uncompromising American writers. But when the Nazis over-ran Paris his income was cut off and he came back to the United States.

His contempt for this country was manifest in everything he wrote, and his vision of America’s future was a hairy thing, at best. In “The World of Sex,” a banned and little-known book he wrote in 1940, he put it like this:

“What will happen when this world of neuters who make up the great bulk of the population collapses is this — they will discover sex. In the period of darkness which will ensue they will lie up in the dark like snakes or toads and chew each other alive during the endless fornication carnival.”

These are the words that came back to haunt him when he moved to Big Sur. No sooner had he settled here, hoping to separate himself from what he called “The Air-Conditioned Night-mare,” than thousands of people sought him out.

When all Miller wanted was a little privacy, they struggled up the steep dirt road to his house on Partington Ridge; if there was a fornication carnival going on up there, they were damn well going to be in on it. At times it seemed like half the population of Greenwich Village was camping on his lawn.

Miller did his best to stem the tide, but it was no use. As his fame spread, his volume of visitors mounted steadily. Many of them had not even read his books. They weren’t interested in literature, they wanted orgies. And they were shocked to find him a quiet, fastidious and very moral man, instead of the raving sexual beast they’d heard stories about. When no orgies materialized cultists drifted on to Los Angeles or San Francisco, or stayed in Big Sur, trying to drum up orgies of their own. Some of them lived in hollow trees, others found abandoned shacks, and a few simply roamed the hills with sleeping bags, living on nuts, berries and wild mustard greens. Miller tried to drive his visitors away but nothing worked. They finally overwhelmed him, and in the process they put Big Sur squarely on the map of national curiosities. Today they are still coming, even though Miller has packed his bags and fled to Europe for what may be a permanent vacation.

The special irony of all this is that Miller has written more about Big Sur — and praised it more — than any other writer in the world. In 1946 he wrote an essay called “This Is My Answer,” which eventually appeared in his book, “Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch,” published in 1958, long after the first invasion.

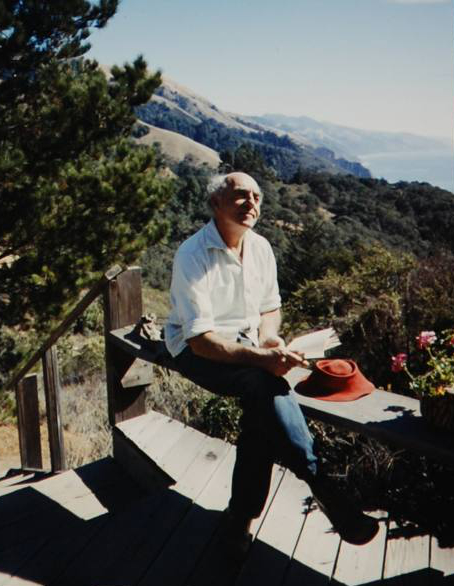

“Peace and solitude!” he says. “I have had a taste of it even in America. Mornings on Partington Ridge I would often go to the cabin door on rising, look out over the rolling velvety hills, filled with such contentment, such gratitude, that instinctively my hand went up in a benediction.”

Miller did his best to stem the tide, but it was no use. As his fame spread, his volume of visitors mounted steadily. Many of them had not even read his books. They weren’t interested in literature, they wanted orgies. And they were shocked to find him a quiet, fastidious and very moral man, instead of the raving sexual beast they’d heard stories about. When no orgies materialized cultists drifted on to Los Angeles or San Francisco, or stayed in Big Sur, trying to drum up orgies of their own. Some of them lived in hollow trees, others found abandoned shacks, and a few simply roamed the hills with sleeping bags, living on nuts, berries and wild mustard greens. Miller tried to drive his visitors away but nothing worked. They finally overwhelmed him, and in the process they put Big Sur squarely on the map of national curiosities. Today they are still coming, even though Miller has packed his bags and fled to Europe for what may be a permanent vacation.

The special irony of all this is that Miller has written more about Big Sur — and praised it more — than any other writer in the world. In 1946 he wrote an essay called “This Is My Answer,” which eventually appeared in his book, “Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch,” published in 1958, long after the first invasion.

“Peace and solitude!” he says. “I have had a taste of it even in America. Mornings on Partington Ridge I would often go to the cabin door on rising, look out over the rolling velvety hills, filled with such contentment, such gratitude, that instinctively my hand went up in a benediction.”

The steamroller of progress has made slow headway in Big Sur. In some spots, in fact, it has bogged down altogether.

To read a New York Times in Big Sur can be a traumatic experience. After living here a few months you find it increasingly difficult to take that mass of threatening, complicated information very seriously. There are people here without the vaguest idea of what is happening in the rest of the world. They haven’t read a newspaper in years, don’t listen to the radio, and see a television set perhaps once a month when they go into town.

Here they didn’t even have electricity until 1947, or telephones until 1958. Compared to the rest of California, Big Sur seems brutally primitive. No subdivisions mark these rugged hills, no supermarkets, no billboards, no crowded commercial wharfs jutting into the sea. In the entire eighty mile stretch of coastline there are only five gas stations and two grocery stores. A fifty mile stretch of the coast is still without electricity. The people who live there — and some of them own whole mountains of virgin land — are still using gas lanterns and Coleman stoves.

To read a New York Times in Big Sur can be a traumatic experience. After living here a few months you find it increasingly difficult to take that mass of threatening, complicated information very seriously. There are people here without the vaguest idea of what is happening in the rest of the world. They haven’t read a newspaper in years, don’t listen to the radio, and see a television set perhaps once a month when they go into town.

Here they didn’t even have electricity until 1947, or telephones until 1958. Compared to the rest of California, Big Sur seems brutally primitive. No subdivisions mark these rugged hills, no supermarkets, no billboards, no crowded commercial wharfs jutting into the sea. In the entire eighty mile stretch of coastline there are only five gas stations and two grocery stores. A fifty mile stretch of the coast is still without electricity. The people who live there — and some of them own whole mountains of virgin land — are still using gas lanterns and Coleman stoves.

It is still possible to roam these hills for days at a time without seeing anything but deer, wolves, mountain lions and wild boar. Pads of Big Sur remain as wild and lonely as they were when Jack London used to come down on horseback from San Francisco. The house he stayed in is still here, high on a ridge a few miles south of the post office. With a little luck a man can still come here and live entirely by himself, but most of the people who arrive don’t have that in mind. These are the transients — the “orphans” and the “weekend ramblers.” The orphans are the spiritually homeless, the disinherited souls of a complex and nerve-wracked society. They can be lawyers, laborers, beatniks or wealthy dilettantes, but they are all looking for a place where they can settle and “feel at home.” Some of them stay, finding in Big Sur the freedom and relaxation they couldn’t find anywhere else. But most of them move on, finding it “too dull” or “too lonely” for their tastes.

The highway alone is enough to give a man pause. It climbs and twists along the cliffs like a huge asphalt roller-coaster; in some spots you can look eight-hundred feet straight down to the booming surf.

The highway alone is enough to give a man pause. It climbs and twists along the cliffs like a huge asphalt roller-coaster; in some spots you can look eight-hundred feet straight down to the booming surf.

The coast from Carmel to San Simeon, with the green slopes of the Santa Lucia mountains plunging down to the sea, is nothing short of awesome. Nepenthe, open from April to November, is one of the most beautiful restaurants anywhere in America; and Chaco, the lecherous old Tsarist writer who, in his words, “hustles liquor” on the Nepenthe terrace, is as colorful a character as a man could hope to meet.

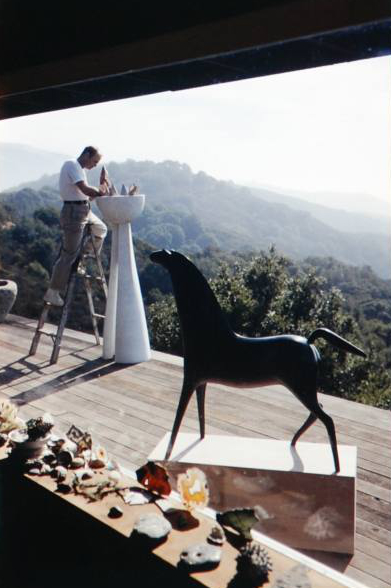

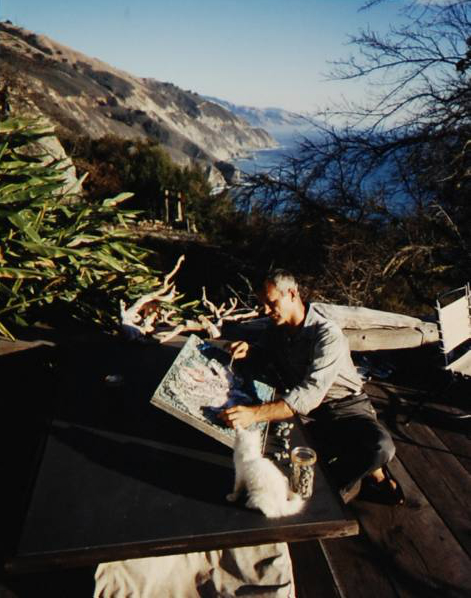

There are plenty of artists here, and most of them exhibit at the Coast Gallery, about halfway between Nepenthe and Hot Springs. Like artists everywhere, many do odd jobs to keep eating and pay the rent. Others, like Bennett Bradbury, drive new Cadillac convertibles and live in “fashionable” Coastlands or Partington Ridge.

On any given day you might walk into the Village Store and find three Frenchmen and two bearded Greeks arguing the fine points of Dada poetry — and on the day after that you’ll find nobody there but a local rancher, muttering to himself about the dangers of hoof-and-mouth disease.

There are plenty of artists here, and most of them exhibit at the Coast Gallery, about halfway between Nepenthe and Hot Springs. Like artists everywhere, many do odd jobs to keep eating and pay the rent. Others, like Bennett Bradbury, drive new Cadillac convertibles and live in “fashionable” Coastlands or Partington Ridge.

On any given day you might walk into the Village Store and find three Frenchmen and two bearded Greeks arguing the fine points of Dada poetry — and on the day after that you’ll find nobody there but a local rancher, muttering to himself about the dangers of hoof-and-mouth disease.

The local poets outnumber the wild boars, but Eric Barker is the only “name”, and he looks too much like a farmer to cause any stir among the tourists. For that matter almost everyone in Big Sur looks like either a farmer or a woodsy poet. People are always taking Emil White, publisher of the Big Sur Guide, for a hermit or a sex fiend; and Helmuth Deetjen, owner of the Big Sur Inn, looks more like a junkie than a lot of real hopheads. If you saw Nicholas Roosevelt, of the Oyster Bay Roosevelts, walking along the highway you might expect him to flag you down, wipe your windshield with an old handkerchief, and ask for a quarter, but he won’t.

To see Big Sur is one thing, and to live here is quite another. The little man who comes down from the city to “get away from it all” — runs amok on wine two weeks later because there is nobody to talk to and the silence is driving him crazy. Big Sur is full of loneliness.

Today the population of Big Sur is smaller than it was in 1900, and just about the same as it was in 1945. Hundreds of people have tried to settle here since the end of the war, and hundreds have failed. Those who come from the cities, hoping to join a merry band of hard-drinking exiles from an over-organized society, are soon disappointed. The exiles are hard to locate, and even harder to drink with. Soon the silence becomes ominous; the pounding sea is too hostile and the nights are full of strange sounds. On some days the only thing to do, besides eat and sleep, is walk up to your mailbox and meet the postman, who drives down from Monterey six days a week in a Volkswagen bus, bringing news-papers, groceries and beer along with your mail.

If you come here looking for something to join or to lean on for support, you are in for a bad time.

In his book on Big Sur, Miller describes the people he found here when he came. Some of them, depressed by the influx of tourists, have left for other, more isolated spots — Mexico, the Pacific Northwest, or the Greek Islands. But many are still living here the same way they were before.

To see Big Sur is one thing, and to live here is quite another. The little man who comes down from the city to “get away from it all” — runs amok on wine two weeks later because there is nobody to talk to and the silence is driving him crazy. Big Sur is full of loneliness.

Today the population of Big Sur is smaller than it was in 1900, and just about the same as it was in 1945. Hundreds of people have tried to settle here since the end of the war, and hundreds have failed. Those who come from the cities, hoping to join a merry band of hard-drinking exiles from an over-organized society, are soon disappointed. The exiles are hard to locate, and even harder to drink with. Soon the silence becomes ominous; the pounding sea is too hostile and the nights are full of strange sounds. On some days the only thing to do, besides eat and sleep, is walk up to your mailbox and meet the postman, who drives down from Monterey six days a week in a Volkswagen bus, bringing news-papers, groceries and beer along with your mail.

If you come here looking for something to join or to lean on for support, you are in for a bad time.

In his book on Big Sur, Miller describes the people he found here when he came. Some of them, depressed by the influx of tourists, have left for other, more isolated spots — Mexico, the Pacific Northwest, or the Greek Islands. But many are still living here the same way they were before.

“These young men, usually in their late twenties or early thirties . . are not concerned with undermining a vicious system, but with leading their own lives — on the fringe of society. It is only natural to find them gravitating towards such places as Big Sur.”

These are the expatriates, the ones who have come from all over the world to make a stab at The Good Life. But there are others, too. Some are ranchers whose families have lived here for generations. Others are out-and-out bastards, who live in isolation because they can’t live anywhere else. And a few are genuine deviates, who live here because nobody cares what they do as long as they keep to themselves.

In some respects Big Sur is closer to New York and Paris than to Monterey and San Francisco. To the writers and photographers who live here just a few months of the year, New York is the axis of the earth — where the publishers are, where assignments originate and where all the checks are signed. And once the checks are cashed, Paris is the next stop. After that it’s keep moving until the money runs out, then back to Big Sur. In their minds, San Francisco is a bar, Monterey is a grocery store, and L.A. is a circus a few hundred miles down the road.

Others, primarily the painters and sculptors, look north to Carmel, with its many art galleries, craft-centers and wallet-heavy tourists.

Visitors in Big Sur — those who are actually invited — are more likely to be artists, foreign journalists or world travelers than, ordinary vacationers. There are no hotels here, the motels are small and devoid of entertainment, and the only night-life revolves around Nepenthe, which is close-d five months of the year.

This is the way life goes in Big Sur: waiting for the mail, watching the sealions in the surf or the dim lights of a ship far out at sea, sitting in the tubs at Hot Springs, once in a while a bit of drink — and, most of the time, working at whatever it is that you came here to work on whether it be painting, writing, gardening or the simple art of living your own life.

These are the expatriates, the ones who have come from all over the world to make a stab at The Good Life. But there are others, too. Some are ranchers whose families have lived here for generations. Others are out-and-out bastards, who live in isolation because they can’t live anywhere else. And a few are genuine deviates, who live here because nobody cares what they do as long as they keep to themselves.

In some respects Big Sur is closer to New York and Paris than to Monterey and San Francisco. To the writers and photographers who live here just a few months of the year, New York is the axis of the earth — where the publishers are, where assignments originate and where all the checks are signed. And once the checks are cashed, Paris is the next stop. After that it’s keep moving until the money runs out, then back to Big Sur. In their minds, San Francisco is a bar, Monterey is a grocery store, and L.A. is a circus a few hundred miles down the road.

Others, primarily the painters and sculptors, look north to Carmel, with its many art galleries, craft-centers and wallet-heavy tourists.

Visitors in Big Sur — those who are actually invited — are more likely to be artists, foreign journalists or world travelers than, ordinary vacationers. There are no hotels here, the motels are small and devoid of entertainment, and the only night-life revolves around Nepenthe, which is close-d five months of the year.

This is the way life goes in Big Sur: waiting for the mail, watching the sealions in the surf or the dim lights of a ship far out at sea, sitting in the tubs at Hot Springs, once in a while a bit of drink — and, most of the time, working at whatever it is that you came here to work on whether it be painting, writing, gardening or the simple art of living your own life.

What — and whom — you find here depends largely on where you look. Partington Ridge, for instance, is Big Sur’s answer to Park Avenue. Nicholas Roosevelt lives there; so does Sam Hopkins, of the Top Of The Mark (Hopkins Hotel) clan. Visiting luminaries are usually quartered on Partington, and when they sit down to eat they are not likely to be served wild mustard greens.

On the Murphy property, including Hot Springs, the combined rental on nine dwellings is $176 a month. This place is a real menagerie, flavored with everything from bestiality to touch football. The barn rents for $15, the farmhouse for $4O, and a shack in the canyon goes for $5. The list of tenants reads something like this: one photographer, one bartender, one publisher, one carpenter, one writer, one fugitive, one metal sculptor, one Zen Buddhist, one physical culturist, one lawyer, and three people who simply defy description — sexually, socially or any other way. There are two legitimate wives on the property; the other females are either mistresses, “companions,” or hopeless losers. Until recently the shining light of this community was Dennis Murphy, the novelist, whose grandmother owns the whole shebang. But when his book, “The Sergeant,” became a best-seller, he was hounded by people who would drive hundreds of miles to jabber at him and drink his liquor. After a few months of this he moved up the coast to Monterey.

Old Mrs. Murphy lives across the mountains in Salinas, and, luckily, gets to Big Sur only two or three times a year. Her husband, the late Dr. Murphy, conceived of this place as a great health spa, a virtual bastion of decency and clean living.

Miller, in one of his rosier moods, said this coast would one day be the Riviera of America. Maybe so, but it will take quite a while. And in the meantime it is one of the finest places in the world to sit naked in the sun and read the New York Times. ●

On the Murphy property, including Hot Springs, the combined rental on nine dwellings is $176 a month. This place is a real menagerie, flavored with everything from bestiality to touch football. The barn rents for $15, the farmhouse for $4O, and a shack in the canyon goes for $5. The list of tenants reads something like this: one photographer, one bartender, one publisher, one carpenter, one writer, one fugitive, one metal sculptor, one Zen Buddhist, one physical culturist, one lawyer, and three people who simply defy description — sexually, socially or any other way. There are two legitimate wives on the property; the other females are either mistresses, “companions,” or hopeless losers. Until recently the shining light of this community was Dennis Murphy, the novelist, whose grandmother owns the whole shebang. But when his book, “The Sergeant,” became a best-seller, he was hounded by people who would drive hundreds of miles to jabber at him and drink his liquor. After a few months of this he moved up the coast to Monterey.

Old Mrs. Murphy lives across the mountains in Salinas, and, luckily, gets to Big Sur only two or three times a year. Her husband, the late Dr. Murphy, conceived of this place as a great health spa, a virtual bastion of decency and clean living.

Miller, in one of his rosier moods, said this coast would one day be the Riviera of America. Maybe so, but it will take quite a while. And in the meantime it is one of the finest places in the world to sit naked in the sun and read the New York Times. ●